By Nadia McGowan.

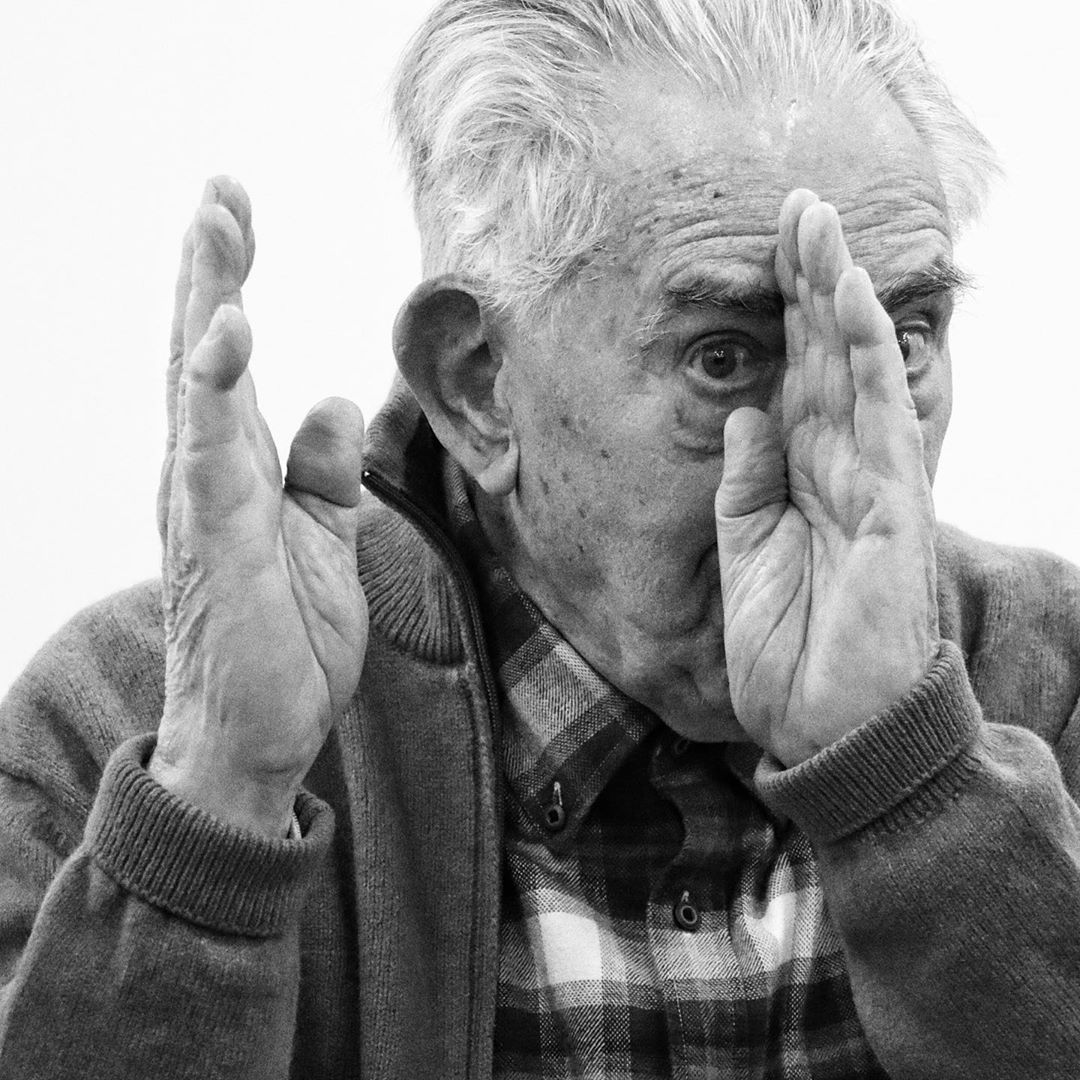

Juan Mariné is, without a doubt, one of the most important cinematographers in Spanish film history. He has inspired generation after generation of filmmakers to the point that many of today’s best cinematographers in his home country call him Master Mariné. He has never ceased to reinvent himself, even now that he has turned one hundred. After a century of experience, he is still a cinematographer, an inventor, a film restoration expert, and a man deeply in love with his profession.

Born in Barcelona on the 31st of December of 1920, Juan Mariné began his filmmaking career at the age of 14 and has shot an estimated 140 films. Within his filmography are some of the most well-known films of their time such as María de la O (Torrado, 1959), La saeta del ruiseñor (Del Amo, 1957) or Sor Citroen (Lazaga, 1967). His legacy does not only live in the past. Recently, for his 100th birthday, the square in front of ECAM film school, where he has had his workshop for years, was named after him in his honour. When last year Migue Amoedo AEC was awarded the TV Academy Talent Award for Money Heist, this became a tribute to Juan Mariné when he presented the award. In the coming months we can expect a documentary about his life and career, directed by Maria Luisa Pujol.

His first film was The Eight Commandment, which he joined purely by chance in 1934. A delivery to the film studio took him to the film set. During shooting, there were constant problems with the camera. Juan noticed that the problem was that the camera assistant had forgotten to plug it in, so he quietly fixed the problem. The director of photography noticed this and told him to come back every single day until the film was finished. And he did.

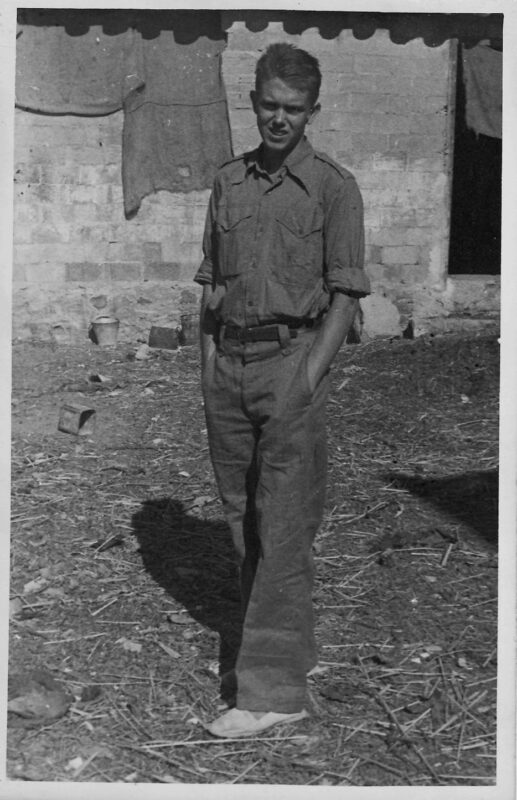

The Spanish Civil war began in 1936 and he was recruited at the age of 17 to fight for the Republican Army. He was sent to the front line without time to even say goodbye to his family. Out of his company of 150 soldiers, he was one of barely thirty survivors. He lost hearing in his right ear due to an explosion and this led to him working as an army photographer, making enlargements of enemy positions.

When the Republicans lost the war, he managed to escape to France, where he was interned into two different concentration camps. To avoid being conscripted into the French Foreign Legion, he handed himself into the Spanish consulate, now under the Franco regime. He was sent back to Spain, incarcerated, and barely escaped being executed.

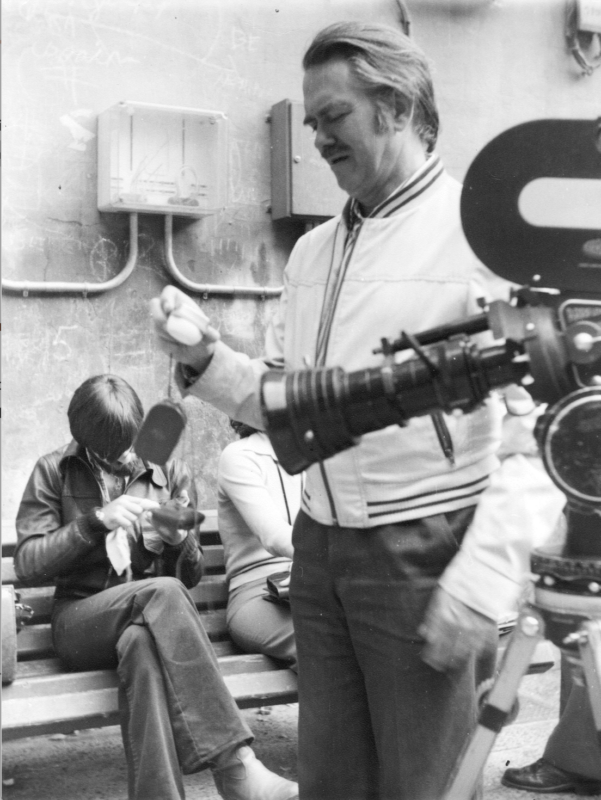

Life was hard for those who fought against the regime. It wasn’t until 1942 that he could work in filmmaking again, in the film Legión de heroes (Fortuny & Seville, 1942). His personality and knowledge soon made him a well-known figure in the Spanish industry and directors such as Edgar Neville, José Luis Saenz de Heredia or Gerardo Herrero were more than happy to work with him. Many directors who worked with him would do so repeatedly. He was also the photographer of the best Spanish actresses, carefully studying their bone structure to portray them in the best possible light. It was during this period that he shot the first Spanish Cinemascope film in Eastmancolor, La gata (Alexandre & Torrecilla) in 1956. We can find traces of the nouvelle vague style in his film Día tras día (del Amo, 1951), with handheld camera and in search for realism, years before the movement started.

His concept of cinematography is that the image lies within the script. Once on location, all that he believes needs to be done is to create the images found in the script, without specifically drawing attention to the cinematographer.

Juan Mariné has also been a researcher and an inventor. He invented anamorphic form glasses and his own high-quality optical printers. His search for higher definition led him to the Mariné Format, a high-definition film stock achieved through a two-perforation negative with the same height of a four-perforation one. This resulted in a larger image area, thus improving resolution.

In the 1980s, he started assisting the Filmoteca on the restoration and archive of the national film heritage. Among his achievements are the invention of a system to wash and hydrate film stock, which has helped restore shrunken and damaged negatives. This machine has been a lifelong project of his, which he began in the 1960s and with which he has restored more than 40 films, among them La aldea maldita (Rey, 1929) or La ciudad en llamas (Marquina, 1944).

Juan Mariné has been awarded the National Photography Award in 1966, the Golden Medal for Merit in the Arts in 1990, the National Cinematography Award in 1994 and the Juan de la Cierva Award for Research in 1974.

Until the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to leave his workplace, Juan Mariné could be found in his personal bunker inside the ECAM film school in Madrid, packed with his equipment and inventions, a space where something is constantly in motion. Students were always welcome and he would share with them his latest work, his thoughts, his counsel.

His great generosity, kindness and passion are unmistakable and always present in everything he does. When the Civil War ended, he promised he would dedicate his life to filmmaking. And so he did. After one hundred years, we can only wish to be lucky enough to share many more moments with him.