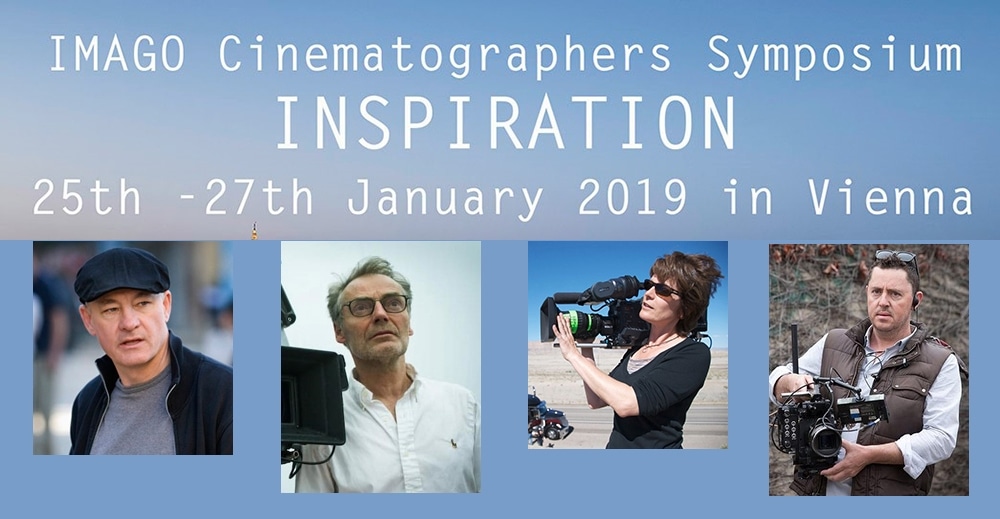

Steen Dalin DFF reports from the IMAGO Symposium in Vienna 25-27th of January 2019

Cover print by Wim Wenders from the exhibition in Metro Kinokulturhaus titled:

Airplane in Monument Valley – 1977

Photo Credit: © Wim Wenders Courtesy of the artist and Blain | Southern London / Berlin

Viennese Waltz – Can not Always be a Dance on Roses

“We have enough inspiration to last us for…? Forever! – This has been the best Master Class Inspiration – ever!” These were pretty much the words by which IMAGO President Paul

|

| IMAGO President Paul René Roestad welcome Vienna Inspiration |

René Roestad FNF summed up the IMAGO event which took place at the start of this year. It was met with applauses from the tightly packed hall of European cinematographers (two of them respectively of Chinese and Brazilian origin, though). As usual, the Danish delegation of DFF constituted the largest national group of foreign guests, only surpassed by the local Austrians. Perhaps the excitement also reflects the fact that the Master Class Committee had engaged three European and one Australian cinematographer, all having made a career in Hollywood. Three of them made it to the semi-final – which is a nomination for the Academy Awards – and probably as close as you can get to an Oscar for Best Cinematography without actually winning it. However, for the first time, not one single American was on stage. That is, just apart from Maryse Alberti, who was born and raised in France. She went as a teenager to the United States and had her entire career across the Atlantic. She was the only one presented at this event without an Oscar nomination, but indeed a cinematographer with an

|

| Jan Weincke and Astrid Verschuur represent the IMAGO Master Class Committee |

impressive backlist and one of the few women, whom Jan Weincke welcomed in his opening speech and expressed gratitude at their increasing numbers. This year the event was fully booked: 160 delegates distributed between 25 countries – and a long waiting list, you might add. Throughout the ten-year lifetime of the committee, four similar events have been held: One in Amsterdam, two in Copenhagen and finally this one was the second time in Vienna. In addition to Jan Weincke DFF, the Master Class Committee consists of Herman Verschuur NSC, Ron Johanson ACS and our Austrian host Astrid Heubrandtner Verschuur AAC, who concluded her welcome speech with some nasty news that tormented her. At the same time as our event, the extreme right-wing forces in Vienna held their annual Akademikerball (Academicians’ Ball, being in the homeland of Johann Strauss). Demonstrations against the Ball could be expected, and the police had closed off a larger area surrounding the Hofburg Palace, just a few hundred meters from our event. Indeed, those of us at the prestigious Hotel Astoria having windows facing the street, couldn’t help but to be awakened both nights by the brawl among the 3000 guests to the Ball and the approximately 8000 opponents. It was a personal matter for Astrid to inform us that only three days earlier, one of these extreme politicians, Minister of the Interior, publicly attacked the European Convention on Human Rights. “Just imagine this”, she said: “Trying to make it socially acceptable to question human rights.” She was deeply shocked and continued: “This is not only happening in Austria, it is the case all over Europe and the rest of the world. In times where we have to face these kinds of movements, all artists like us cinematographers have to stand up against this insanity which is growing everywhere.”

Wenders & Müller – the Dynamic Duo

|

| Wim Wenders at the inauguration of the exhibition |

Four years ago, the IMAGO Inspiration took place in the Stadtkino im Künstlerhaus, near to the Metro Kinokulturhaus where we were staying now. But at that time the residence could not house Inspiration, due to extensive restoration. But now this magnificent Kinokulturhaus has reopened, hosting a Cinematheque, a Film Archive and two floors of state-of-the-art Exhibition Halls. It presented a retrospective exhibition on Wim Wenders, which he himself personally inaugurated only a fortnight prior to our arrival. The entire exhibition glitters in all its whitened purity, displaying the director’s own preferred polaroids and his black and white photographs along with quotes from his diary of the various film recordings – everything resembling pieces of contemporary art. An exhibition that could easily take place in many European art galleries and museums. His distinctive images describe the twenty years of filmmaking with Robby Müller NSC, which started very early in the 70s producing titles such as: Alice in den Städten and my absolute favourite, the black and white, three-hour-long Im Lauf der Zeit, followed by Der amerikanische Freund, until the partnership ended miserably in 1991 with Bis ans Ende der Welt. At that time their friendship had deteriorated and they split once and for all to go separate ways. Wim Wenders continued his cinematographic expeditions around the world, while Robby Müller joined forces with Jim Jarmusch and Lars von Trier among others.

|

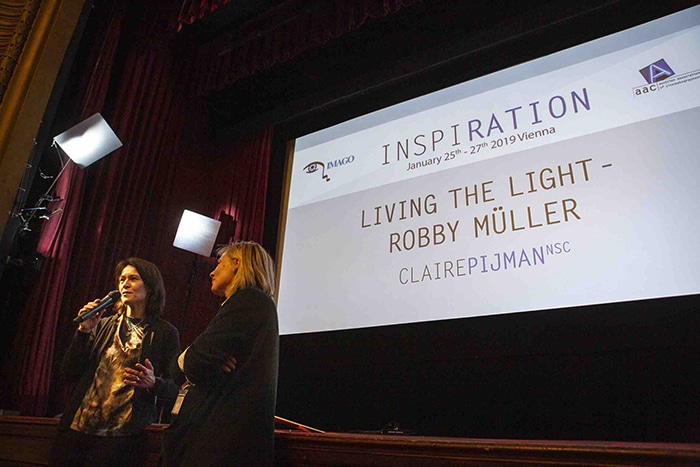

| Exhibition Halls at the Film Archive |

All of this and even more were confirmed in the cinema on Friday night, when the above-mentioned Astrid Verschuur had Claire Pijman NSC in the ‘hot seat’ for a conversation before the screening of her documentary Living the Light. Since the premiere in Venice last year it has toured at numerous festivals and film schools in Europe, including our own in  Copenhagen in collaboration with DFF last November. Right now, Claire Pijman and her entourage are “praying for a good American premiere,” as she puts it. Robby Müller was living his life through the lens of a film camera. When he wasn’t working professionally, he compensated using his video camera. He simply filmed EVERYTHING: His parents, his girlfriends, his dogs and his daughter, who in Claire’s documentary seemed pretty fed up by always watching her father on the other side of a camera. But in his studies of hotel rooms, of the street downstairs, of the Edward Hopper-like urban landscapes in the United States – and outside in the wild: Birds in flight transforming into light reflections and withered leaves in flowing water – in those videos you get to know his search for scenes and moods. Later they appear in the movie clips Claire Pijman quite intelligently had selected and merged with the endless Hi8 recordings that she got access to with his permission. Robby Müller died in April last year, but he got to experience the exhibition Master of Light at EYE in Amsterdam 2016, and also had the opportunity to watch the documentary several times according to Pijman, which is either ironic or just miraculous, as he would never even watch his own video footage – he was just filming.

Copenhagen in collaboration with DFF last November. Right now, Claire Pijman and her entourage are “praying for a good American premiere,” as she puts it. Robby Müller was living his life through the lens of a film camera. When he wasn’t working professionally, he compensated using his video camera. He simply filmed EVERYTHING: His parents, his girlfriends, his dogs and his daughter, who in Claire’s documentary seemed pretty fed up by always watching her father on the other side of a camera. But in his studies of hotel rooms, of the street downstairs, of the Edward Hopper-like urban landscapes in the United States – and outside in the wild: Birds in flight transforming into light reflections and withered leaves in flowing water – in those videos you get to know his search for scenes and moods. Later they appear in the movie clips Claire Pijman quite intelligently had selected and merged with the endless Hi8 recordings that she got access to with his permission. Robby Müller died in April last year, but he got to experience the exhibition Master of Light at EYE in Amsterdam 2016, and also had the opportunity to watch the documentary several times according to Pijman, which is either ironic or just miraculous, as he would never even watch his own video footage – he was just filming.

1977_Airplane in Monument Valley.

1977_Airplane in Monument Valley.

Photo Credit: © Wim Wenders Courtesy of the artist and Blain|Southern London/Berlin

Two British Photographers – and Ken Loach

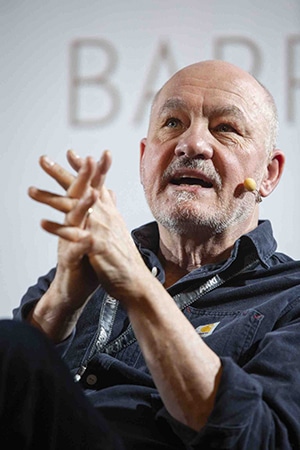

Back to the Metro Kinokulturhaus, on the ground floor in the heart of the building the space opens up to a wonderful carefully restored Baroque theatre dating back to 1840. First man on stage was Barry Ackroyd (moderated by Volker Gläser AAC) who in 2014 took over the post as President of the British Federation BSC. He turned out to be a very pleasant and

|

| Barry Ackroyd BSC |

charming man with a low-key English humour. Characteristics that he attributed to his director over many years, Ken Loach. In the same spirit, but rather unusual in such master classes, he started a selection of three clips from films he had NOT photographed himself: First of all, Kes (Ken Loach 1969), this 16mm grained classic brought tears in the eyes of the older segment of the cinematographers. Then The Killing Fields (Roland Joffé 1984) and finally The Mission (Roland Joffé 1986). All three films photographed by Chris Menges BSC, who had supported Ackroyd in the leap from documentary to feature film. He also made Ackroyd join the British Society of Cinematographers and, in general, served as his mentor and source of inspiration. One day Ackroyd received a phone call from Ken Loach himself: “He’s a humble man and said: “You’re probably very busy, you probably don’t want to work with me.” My answer was: “I do – I do!” This resulted in the first film Riff Raff (1991) together with his idol and furthermore in a 25-year long collaboration over 12 films. It was a continuing learning process at the ‘Ken Loach University’ that he would never forget. There was a reason for everything Loach did: The observing, the long lenses and the documentary style that Loach himself admitted having learned from Chris Menges. When Barry one day ventured to bring a lamp into a location, Ken Loach exclaimed: “Oh, it’s very bright isn’t it! Do you think the actors would like that?” Their last film together was The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) which Ackroyd considers to be Ken Loach’s masterpiece.

|

| The Hurt Locker – first Oscar to a female director |

But the inspiration he got from Ken Loach and Chris Menges became the foundation stone, upon which he later built his entire career in collaboration with many directors: Paul Greengrass, Sean Penn and Kathryn Bigelow, who was the first female director to win an Oscar in 2009 for The Hurt Locker. The film also brought a personal Academy Award nomination to Barry Ackroyd. In these later films, you clearly trace his development of the Ken Loach techniques, now with 3 or 4 digital cameras cross-covering the scene. Each camera operator has full freedom to improvise and to zoom at will – no use of fixed (and locked) optics. The method has both advantages and disadvantages, he believes, but the limitation always lies in the amount of equipment that you carry to the set. He described how he always places the cameras outside the circle formed by the actors. Inside the circle they have full freedom to move around. When shooting outdoor he moves with the sun during the day, so that the actors always are lit from behind.

Towards the end Barry Ackroyd moved into philosophical considerations about the cinematographers’ choice of films. “You’re stuck with a bunch of manuscripts thinking: “They have sent me twenty scripts – Why? I have no idea!” You have to choose your movies with care and for the right reasons. He believes that movies are a very strong political medium and there is a clear difference between Hollywood and the European approach. He classifies the European style as simply ‘films’ while the American ‘movies’ primarily are entertainment. “Hollywood will make it into something I would not like to see myself.” Encouraged by the audience, he admitted that the action film he made with Paul Greengrass in 2016, Jason Bourne, which was the fourth out of a series of swashbuckler movies with Matt Damon – indeed was one of these kind of Hollywood ‘movies’.

Danish Delight

Saturday morning was the master class which was anticipated with excitement by the group of DFF, namely the Master Class with Dan Laustsen ASC DFF. Astrid Verschuur

|

| Astrid Verschuur AAC introducing Andreas Fischer-Hansen DFF former IMAGO president and Dan Laustsen DFF |

introduced Andreas Fischer-Hansen DFF as his moderator and was delighted with the fact, that Andreas had also been Dan’s teacher at the Film School. It took off quite well. Together they had prepared an informative and humorous conversation that Andreas began by saying: “Yes, I’ve known Dan for quite a few years. He came to the film school as a still photographer and wasn’t very interested in film, but he thought – let’s give it a try! Or maybe he was interested but he wasn’t very keen. And now he’s one of the great cinematographers of our time. He was very young – and so was I – in fact – more than 40 years ago.” All to a lot of smiles and a great applause from the audience, after which Dan continued telling that as a 22-year-old youngster he had trained himself to be a fashion photographer and really had no idea what to do next.

|

Not one drop of water in this scene from The Shape of Water |

His older sister had just read about the Film School in the newspaper and urged him to apply. For the interview he didn’t understand the topics put to him by the teachers were all about. He was unaware of Bertolucci and Storaro and had never looked through the viewfinder of a film camera: “I didn’t know what they were talking about, but then I got a letter saying “Welcome to the Danish Film School” and that was my start but I was totally lost. Andreas added that at the time it was very difficult to get close to film equipment, so at the Film School they focused largely on still images in the process of selecting candidates.

Dan continued: “Then I shot some features in Denmark and some features in The United States and then I shot a movie called John Wick…” – “You shot quite a few films in Denmark?” Andreas interrupted, but unfortunately, we did not get to see any clips from Dan’s multiple Danish productions with Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, Rumle Hammerich, Åke Sandgren, Ole Bornedal, Lisa Ohlin and many, many others. It would have been interesting to watch a historical cross section in which one could have sensed the development of his work.

A Voice in the Dark

Instead, we watched a clip from John Wick. An American franchise (i.e., a continuing series of films) created by the two partners Chad Stahelski and Derek Kolstad, who served as

|

| John Wick – lots of guns and not that much dialogue |

stunt doubles for Keanu Reeves in The Matrix Trilogy. In 2014 they brought the same Keanu Reeves to the first John Wick movie that Dan did NOT shoot. But Reeves also holds the title role in the next two films with Dan Lausten. Then two more clips from John Wick was shown in continuation. They were immense action with a lot of violence, guns, stunts and not much dialogue – in fact, no dialogue at all, except for the last clip when a voice outside the frame sneered something in French, which in an American movie often points to the villain.

I was struggling to put some words together in English for the Q&A, when suddenly a voice rose from the audience: “Using the skills of cinematographers in storytelling – the inspiration looks to me inspired by Leni Riefenstahl. We see every day problems in the news of criminal action. Now, are we as cinematographers helping these things to be accepted on a social level?” Dan quickly responded: “Of course you’re totally right. But it’s a very long discussion. Some of the movies you’re doing are from your heart and some of them are like… ” The voice from the dark continued: “Sure, but it is also a question of responsibility. We are making films for people who are watching them in cinema, and they might be fantastic from a technical point of view, although I got the impression that the message is just – how can I show brutality?”

Dan replied: “For me it’s not brutality – for me it’s just like a kind of cartoon. People are getting killed but nothing happens. It’s not like you’re seeing people in close up getting smashed – I think John Wick has that – it’s kind of a cartoon, everything can happen. But I understand what you’re saying and I respect that, but it’s not the way I live my life. I like these kinds of movies and I think it’s great to do.” Surely Dan might have a point: John Wick is a cartoon character. Those repeatedly violent fights have the character of a ballet, and the many

|

frequent homicides by firearms have the resemblance of boyish pranks in the schoolyard: “Bang-bang, you’re dead,” rather than realistic, blood-dripping scenarios.

During the break I sought out the mysterious voice, which belonged to Frédéric-Gérard Kaczek AAC. He is well known in the inner circle of IMAGO and talked to me about the possibility of creating some form of ethical committee within IMAGO that could address the issue. And that is indeed an exemplary motivation: Doesn’t film and television contribute to legitimize the increasing use of violence and firearms in schools and gang conflicts by exposing the violence so much? You can also turn the issue upside down and ask the cinematographer: “Which offer would you rather turn down – a film of violence or a porn movie?” If choosing the latter, we may be heading towards American standards where guns are socially more acceptable than the naked breast of Janet Jackson. Anyway, the discussion had the side effect that Frédéric-Gérard was subsequently subjected to friendly bullying each time a clip containing violence was displayed: “Sorry Freddy, but there will be some violence in the next clip.”

Mexican Water

After the break, the master class of Dan and Andreas was saved in the nick of time – by Guillermo del Toro, with whom Dan Laustsen has made three films: Mimic (1997), Crimson Peak (2015) and The Shape of Water (2017). The last film literally vacuuming the Academy Awards for Oscar nominations in 2018, with a total of 13 nominations of which the nomination for Best Cinematography included Dan Laustsen. With the Mexican director we went into a completely different ball game of poetic storytelling. The clips from those last two films dissolved the cramped mood in the audience into an exciting applause that fell like redeeming rain. Especially the opening sequence of The Shape of Water was remarkable.

|

| Omar Al-Rawi from the Mayor’s office and Marijana Stoisits from the Vienna Film Commission invited to Heurigenrestaurant. Flanked by Astrid and Paul René |

It looks like a tracking shot through an apartment filled with water, the entire interior, chairs, tables, a clock and a table lamp, even the sleeping woman on her sofa, floats dreamingly around in the room. Dan revealed that not a single drop of water was involved. It was a steadicam with 48fps slow motion and all of the furniture and the woman was suspended in wires. The waving light reflections were made by video projectors and only the fish and the hair of the protagonist are made with CGI. Take a moment and enjoy the clip on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcX_UO-wKZo

Similar to some of the other cinematographers, Dan pointed to the importance of generating as much as possible in the camera, instead of leaving it to the computer guys later. It is part of the process of controlling the image. The texture of water was made of smoke, which created a horrible working environment for the crew, Dan added. The major problem during filming was Guillermo del Toro’s tendency to record everything in continuity, resulting in a constant brake down and rebuilding of the sets, as well as the need for relighting the scene after each take.

It was really quite remarkable how many of the non-Danish delegates present, who repeatedly asked for film clips from Dan and Ole Bornedal’s TV series 1864 (the year of an armed conflict between Denmark and Germany). This was a major production in Denmark, which in Dan’s Hollywood optic was a low budget television show. But apparently the Europeans knew it from Netflix. In the absence of clips from 1864, Dan offered anybody interested to watch a trailer on his iPhone during the break.

|

| Maryse Alberti and Claire Pijman on stage |

The afternoon was devoted to an excursion, a walking tour sightseeing at the centre of Vienna – a bit disappointing in pouring rain! The many imposing castles and mansions reflect a not so distant past, when Vienna was the centre of the mighty Austrian-Hungarian Empire. The trip ended at the Hofburg Palace, where the nightly fights took place and where Hitler from a balcony in 1938 held his victory speech after the Anschluß – the annexation of Austria in the Third Reich. In the evening, the Mayor and the Vienna Film Commission invited the whole group of cinematographers for a dinner at a traditional restaurant located in Neustift am Walde, a bit up the wooded mountains surrounding the city. This was a wonderful opportunity to socialize and to get acquainted with the other delegates from many countries.

Waltz – with Wrestlers

The first two days went quickly with only one master class per day, whereas the Sunday in contrast consisted of two large ‘classes.’ To start Maryse Alberti, who was the only one of the four protagonists, that didn’t have her name provided with three letters, indicating an association. When inquired, she excused herself from not having had the time – that it’s quite expensive with a membership of the ASC, and in addition she lives in New York – very far from Hollywood. But during the Saturday night party, Dan Laustsen almost convinced her in joining the ASC. This time Claire Pijman appeared in the role as her moderator. As a 19-year-old girl, Maryse Alberti went from France to the United States. She was hoping to experience Jimi Hendrix live, but rather unfortunately he deceased prior to her arrival. Instead, she made the ‘classic’ pilgrimage ‘go-west’ travel, hitchhiking for three years with a Kodak Instamatic camera. When she finally returned to New York, a handful of these instamatic images turned into an exhibition. In the 70s, the city was a pretty “crazy place” on the art and rock scene. With a gift from her boyfriend, a Nikon, she began photographing good friends and rock bands. That led to a job at the New York Rocker magazine, for which she provided photos of Lou Reed, Iggi Pop, Frank Zappa and many others. Through a friend she obtained a paid job as a photographer on X-rated films. “It was my first entrance to the world of film: Two years with Rock & Roll and X-rated! That was my film school, because at the set I met a lot of students from NYU and Columbia University.”

|

| A break in the schedule. Maryse Alberti and Dan Laustsen |

Then in 1990 she got hold of a 16mm camera and with her friend Stephanie Black, they made the documentary H- 2 Worker about the exploitation of Jamaican guest workers at the cane plantations in Florida. The film made it to Sundance and won prices for best documentary and best cinematography. Now she was on the map and continued the next 15-20 years making several documentaries and some low budget fiction films. When you take a look at her backlist, it looks like a ballot paper for the parliamentary election in Denmark (lots of parties and candidates). Among the heap of titles some names stand out: Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, Martin Scorsese and Laurie Anderson. Her breakthrough in Hollywood was with The Wrestler (2008) by Darren Aronofsky. It won a Golden Lion in Venice and went victoriously around the world to finally end up with two Oscar nominations. Mickey Rourke, who previously had a boxing career, fits perfectly into the environment of hard-boiled American wrestlers as a has-been fighter. The cinematography of Maryse Alberti contributed to the authenticity of the film, without big budget artificial lighting and with her 16mm camera constantly following Rourke. Especially during the turbulent scenes in the ring, when the camera moves close up in a floating ballet between the combatants. Claire Pijman asked her if the experiences from making documentaries was an advantage in her shift to fiction: “It is essential, you really learn to react to something that is in front of you, and in documentary you don’t have time to think. Work fast and know where to be with the camera. The camera movements, the coverage – all that can be applied to fiction.”

The success of the film wheeled into another Oscar nominated production in the same category (curiously none of them received a nomination for best cinematography, though). After 30 years and six films with Sylvester Stallone performing the role of Rocky Balboa, the series suffered from distinct metal fatigue. But in 2015, director Ryan Coogler breathed new life and blood into a sequel: Creed (both he and the protagonist Michael B. Jordan being African Americans). Sylvester Stallone reappears in a supporting role as a coach to Jordan. The camera of Maryse Alberti certainly contributed to the dramatic look of the film, reviewed by the critic as the best Rocky movie ever. Having seen some examples, we were treated to clips from her latest production Chappaquiddick, supposedly only to be seen on Netflix but not in cinemas. In the UK it was renamed into The Senator, obviously because it is a tale about the Ted Kennedy scandal in 1969, when the youngest and surviving Kennedy brother drove his Oldsmobile off a small wooden bridge. He escaped the scene only to leave a young woman to her death by drowning, thereby

|

| Maryse Alberti and the director John Curran at Chappaquiddick |

causing havoc to his presidential ambitions. For these Hollywood productions, Alberti generally had to use camera operators, being in the driver seat as a DOP. When teased by crew members for being a petite woman working in a physically demanding job, she is quoted for replying: “The little lady doesn’t carry the big lights. She points and the big guys carry the lights.”

Waltzing Matilda – in the Light of LED

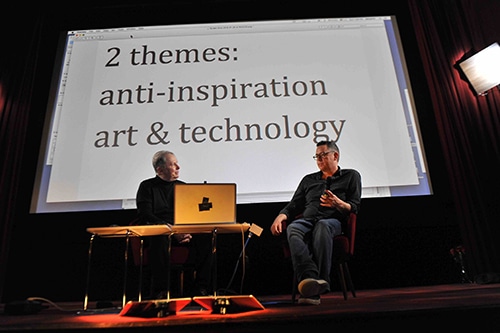

Last MAN on stage was Greig Fraser, member of both ASC and ACS. His mediator Benjamin B is quite difficult to Google, but when you discover the surname Bergery a versatile man emerges, affiliated to several associations (AFC, FSF and NSC), organizer of numerous master classes, blogger at The Film Book and correspondent at American Cinematographer. Hence the Australian was in good hands. However, or maybe it’s just me, but it was somewhat annoying that they continued their talk during the movie clips – it’s like hell to take notes in the cinema darkness! Like Barry Ackroyd, Fraser too worked with Kathryn Bigelow, but it was five years earlier on Zero Dark Thirty, about the CIA’s hunt for Osama Bin Laden. The aesthetic of the film reveals that it now has become technically possible to film in almost total darkness and thus increase realism. Both of them thought that there is a tendency in the film industry to downgrade the technique. But cinema sure is a technological art form. Admittedly, film stock and development are no longer work tools, but never before have the possibilities been so versatile. So many digital cameras exist and so do an abundance of different lenses like never before. Not to mention the development of LED lights. “Things in the last five years have just jumped so far ahead, that ten years ago, if you were talking about RGB coloured LED that can light up an entire Star Wars movie – it would have been like: “Stop – you’re crazy. There’s no way you can use LED to shoot a big budget movie.” But that was exactly what Greig Fraser did on Rogue One: A Star Wars Story just three years ago, but more on that later.

Suddenly the entire seminar theme, Inspiration, was turned into a question of anti-inspiration: Not to let yourself be distracted by external influences. The good advice was: “Stop watching movies – it’s not gonna help you.” Then they introduced a rather comprehensive showcase: “The program is going to be pretty tough. It turns out, it’s a bunch of films about the United States of America. And it’s also about violence. So I have to warn you guys: There will be violence! I’m certainly going to hear from certain members in the audience about this,” which caused many laughs and much applause from the audience, because this was just a final allusion from the ‘teacher’ to our all-time ‘Freddy’ – just like in the childhood school classes.

Dances with Bullets

The first (violent) film clip was Killing Them Softly (2012), an American neo-noir-action-thriller-crime-movie by Andrew Dominik and starring Brad Pitt. “A story about America, the mafia, business – and the business of killing,” Greig Fraser added. A film depicting the death of political idealism in America that rather let a quick-witted Donald Trump govern than an

|

| Benjamin Bergery moderating Greig Fraser ACS ASC |

irresolute Barack Obama – four years before it actually happened. The film was made at the end of the celluloid era and his own favourite raw stock was 5230. Unfortunately, Kodak had stopped production, but Greig phoned a NYU student whom he at one point had given some leftover rolls. This guy only found a piece of 15 meters among the vegetables in his freezer. It was sent to Kodak in San Francisco and, based on its composition analysis, the laboratory managed to recreate a 5230 film stock from its DNA so now the stock once again is available – a story virtually torn out of Jurassic Park. Most remarkable was the scene of Brad Pitt shooting a victim through a car window. The director gave him the task: “Please pan the camera with the movement of the bullet.” Some among the audience would like to know whether it was CGI or not, but apparently it was real life cinematography. The solution was a ‘camera’ with a rotating mirror, which beams the image on a piece of film fixed in a centrifuge that spins at a stupendous speed obtaining 500,000 fps. The C4 Rotating Mirror High Speed Camera was

|

| Greig Fraser ACS ASC |

originally developed during the 1950s to record experiments with nuclear blasts. Once again it was an example of the effort to do as much as possible in the camera, perhaps using glass plates and other old-fashioned techniques. ”I feel there is an overwhelming move back to real shooting, and I help push as much as we can, because CGI is a marvel advance, but I still believe – if it looks like CGI it has failed.”

He brought this concept further to Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016). The landscapes were shot with painted canvases in the background, just as it was done in the old times of silent movies. “Instead of using black backgrounds and then have visual effects to fix everything.” Greig Fraser added. It was with some nerve he accepted a Star Wars movie, partly because they were the great adventures of his childhood, and partly because he memorized the shiny helmet of Darth Vader with fear: “As a student when I was learning the technic of lightning, I was thinking: Thank goodness I didn’t have to do this guy – it’s a pain in the ass. He’s black and he’s got reflections everywhere.” But when he found himself on set in the studio surrounded by X-wing fighters, he felt like a 4-year-old kid again.

|

| The entire group from DFF in front of Metro Kinokulturhaus |

Well, now I have to skip several movies and finish off with Lion. The debut movie of director Garth Davis that obtained six Oscar nominations in 2017, including one to our protagonist cinematographer. He and the director were introduced in their youth at a studio in Melbourne “by a Danish gentleman called Leif Schiller.” In addition, Greig’s upcoming wife had worked in India for several years, so it was a sentimental journey to both of them returning to Calcutta. “Is it correct that you married in a helicopter?” Benjamin B asked. “Yes we did. At the same time I faced two of my greatest fears: Commitment & Heights!” Getting back to the movie: It unfolds around a four-year-old Indian boy (the title person Lion) who inadvertently gets away from his family and ends up alone in a train heading to Calcutta. He is later adopted by an Australian family (David Weham and Nicole Kidman) and does not reunite with his Indian family until he is an adult. It is an adaptation of a real-life story – A Long Way Home – written by Saroo Brierley, the actual Lion. “The Indians have a very long history of making movies, but they do it in such a big way. They use the lack of physical resources by having lots of people. That’s kind of the antithesis to how we wanted to work: Quite nimble and small – not to be bucked down in equipment.” They shot the entire start of the movie of the little boy running through the Indian crowd of people with only three LED digital spots (brand new at the time).

We missed the rest of the movie – and Nicole Kidman – as time was up and everyone was preparing to go home. Benjamin B completed the IMAGO Symposium with a simple question to the audience: “Is the cinematographer an artist? Yes or no?” There was no doubt about the outcome and in a final wrap up, all of European cinematograpers were portrayed in the ancient cinema. The only thing left to do was the obligatory group photo of the Danish DFF delegation in front of the Metro Kinokulturhaus. Yes, and then Denmark won the World Handball Championship by beating Norway on our way back home.

The cinematographers gathered in the theater at Metro Kinokulturhaus

The cinematographers gathered in the theater at Metro Kinokulturhaus

Photo credits:

Front Page Photo Credit: © Wim Wenders Courtesy of the artist and Blain|Southern London/Berlin

Wim Wenders exhibition: FOTOS: @ FILMARCHIV AUSTRIA / SEVERIN DOSTAL

Photo by Francois Duhamel – © 2011 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

IMAGO photographers: Bettina Frenzel / Reinhard Mayr AAC

DFF photographer: Poul Lystrup Thomsen

Editorial:

Editing & translation: Steen Dalin

(with a little help from friends)