Vladan Pavic’s journey into cinematography is a compelling narrative of discovery, adaptation, and perseverance. Born and raised in Belgrade, Serbia, Pavic’s early life was shaped by a mix of artistic influences and technological curiosities. His story is one of resilience, creativity, and a deep connection to his cultural roots, all of which have defined his career as a cinematographer and educator.

Pavic grew up in a family deeply rooted in the arts. His father was a poet, and their home was filled with books and paintings, fostering an environment that leaned naturally toward creativity. His initial foray into the world of visuals came through photography, using his father’s old Soviet plastic camera, the Smena 8, during childhood trips. Though it started as a hobby, this early engagement with imagery planted the seeds for his future career.

In high school during the mid-1980s, Pavic shifted focus to technology, becoming fascinated by early personal computers like the Spectrum 48 and Commodore 64. His love for computers mirrored the emerging digital age, though he eventually found his way back to art. It was during this period of experimentation that he began to devour books on film and cinematography, leading to a pivotal decision: leaving his civil engineering studies to pursue his true calling at Serbia’s National Film School.

Enrolling in film school during the tumultuous 1990s, Pavic found himself in a country grappling with war and economic crisis as Yugoslavia transitioned from socialism to capitalism. For Pavic, cinematography became a form of escapism—a means to focus on creative expression amidst the chaos. His time in film school was transformative, and a defining moment came when he participated in a prestigious masterclass in Budapest, hosted by Oscar-winning cinematographers. His work there, praised for its innovation, solidified his confidence and propelled him forward.

Like many young cinematographers, Pavic began his career shooting music videos and commercials. The 1990s saw the rise of digital technology, and Pavic embraced it enthusiastically, experimenting with early digital video cameras and post-production techniques. His big break came in 2000 when he received a phone call inviting him to shoot his first feature film. Despite the challenges—such as working without a script—it was a milestone that tested his abilities and marked the start of his “real career.” Reflecting on this period, Pavic cites: “What doesn’t break you makes you stronger.”

Beyond his work behind the camera, Pavic is also a dedicated professor at Serbia’s National Film School. Teaching has become an integral part of his life, allowing him to stay connected to the younger generation and pass on the knowledge and inspiration he has accumulated over decades. “Teaching keeps me fresh and updated with current trends,” Pavic explains. “It’s a wonderful job that makes me feel younger. I learn alongside my students, and it’s a process that keeps me motivated.”

Pavic emphasizes the similarities between teaching and leading a film crew. “Whether you’re working with students or a film crew, it’s about understanding people, motivating them, and unlocking their potential,” he says. “It’s not just about giving orders; it’s about building trust and creating an environment where everyone feels inspired to contribute.”

Serbia’s rich cultural history and complex identity have deeply influenced Pavic’s visual sensibilities. “We are at a crossroads between East and West,” he notes. “Our architecture, cuisine, and art reflect a mix of Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian influences.” This unique environment, with its chaotic blend of styles, shaped Pavic’s perspective, giving him a broader visual palette.

Growing up in socialist Yugoslavia also played a role. Unlike the restrictive regimes of some Eastern Bloc countries, Yugoslavia under Tito allowed for travel and exposure to Western culture. “We had access to Western music, films, and art, which enriched our perspectives,” Pavic recalls.

Pavic credits films like Delicatessen (1991) by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and A Short Film About Killing (1988) by Krzysztof Kieślowski as key inspirations. He admires the innovative use of filters, lighting, and color manipulation in these works, techniques that continue to inform his approach to cinematography. One film that left a profound impact on Pavic is Come and See (1985), a Soviet war film directed by Elem Klimov. “It’s one of the best films ever made about war,” Pavic says. “The way it uses raw, unfiltered imagery to convey the horrors of war is unparalleled. The 1980s and ’90s were particularly interesting for cinematographers because of the advent of high-speed film materials. These advancements gave us greater opportunities to experiment with diffuse light, which became a defining feature of many films from that era.”

As a cinematographer, Pavic has witnessed—and adapted to—the dramatic shift from analog to digital technology. While he acknowledges the advantages of modern tools, such as LED lighting and high-speed cameras, he remains grounded in the fundamentals. “The most important thing is where you put the camera and how you frame the story,” he says. For Pavic, technology is a tool, not a substitute for creativity.

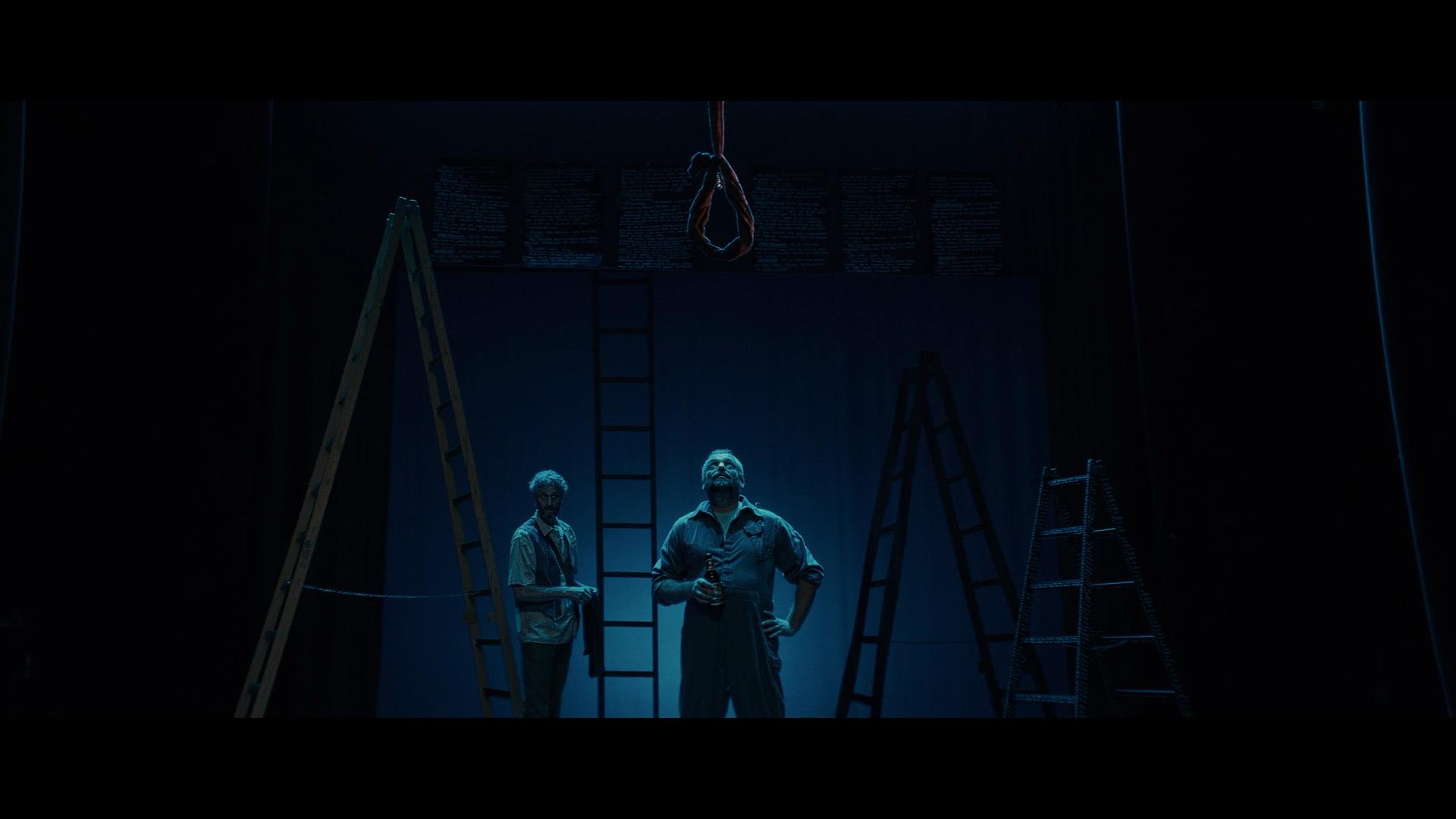

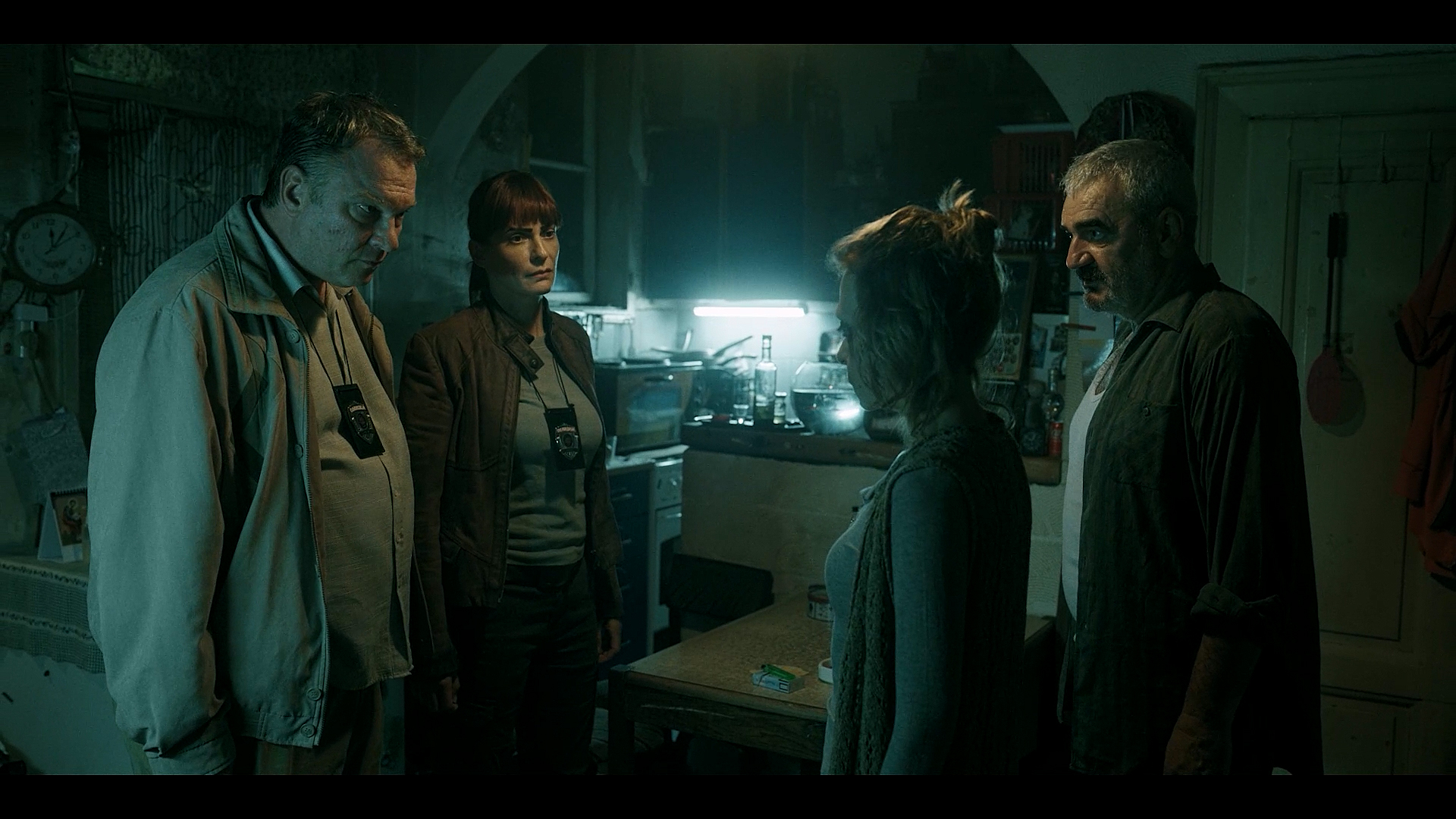

Pavic’s recent work includes TV series like Nemini and Constantine’s Crossing, a period drama set after World War II that blends mystery and historical elements. “It’s a kind of marathon,” Pavic says of working on TV series, contrasting it with the shorter, more intense process of feature films. He is currently preparing for the second season of Constantine’s Crossing, which will be shot using two Alexa 35 cameras and features an intricately designed backlot set that blurs the line between reality and fiction.

For Pavic, cinematography is about translating stories into images. “It’s like composing a symphony,” he explains. “You have all these elements—light, color, space, rhythm—and you combine them to create something that moves and resonates with the audience. It’s a process that’s both technical and deeply artistic.”

Vladan Pavic’s career is a testament to resilience, adaptability, and a deep commitment to the art of cinematography. From navigating the challenges of growing up in a turbulent country to embracing the rapid evolution of filmmaking technology, Pavic has remained dedicated to his craft. Today, as both a filmmaker and educator, he continues to inspire others while pushing the boundaries of visual storytelling, leaving an indelible mark on the world of cinema.

“It’s hard to present yourself in words,” Pavic concludes. “My works—my films, TV series, and the students I’ve taught—will tell my story better than I ever could.”