A courtesy of the Global Cinematography Institute

www.globalcinematography.com/courses

written by Yuri Neyman, ASC

Early 1900’s

“The beginning of artistic expression…”

(Excerpts from Yuri Neyman, ASC’s book: “The Visual History of Styles in Cinematography” (in progress). © All Rights Reserved.)

Film technology was not originally created for artistic expression. It began as a commercial interest and a simple extension of recording live theatrical events with documentary reproduction. As Herb Lightman, legendary editor of American Cinematographer from 1965-1982, notes, “Camerawork was not thought of as having any aesthetic potentialities of its own” during the early 1900’s.

Film technology was not originally created for artistic expression. It began as a commercial interest and a simple extension of recording live theatrical events with documentary reproduction. As Herb Lightman, legendary editor of American Cinematographer from 1965-1982, notes, “Camerawork was not thought of as having any aesthetic potentialities of its own” during the early 1900’s.

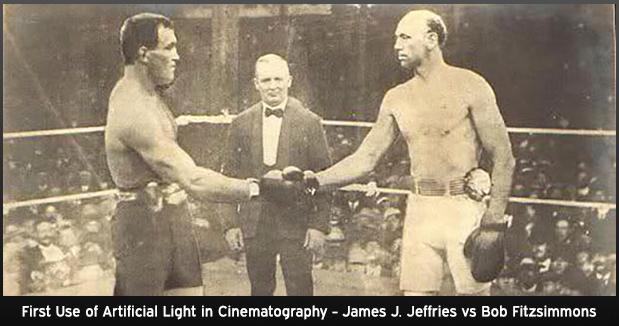

The first documented use of artificial lights took place to allow filming of the James Jeffries-Bob Fitzsimmons boxing match. The outdoor stages were equipped with sheets of silk diffusion material or other translucent cloth manipulated by pulleys. The cameraman could thus adjust the amount of sunlight on the actors.

These diffusers served to soften the light and cut down on the harsh contrast. Soon, reflectors were employed in conjunction with the diffusion material. Using mirrors or polished metal surfaces, the cameraman could reflect sunlight into the shadow areas of the set to create an evenly illuminated and more pleasing picture, though this never rose above pure documentary recreation.

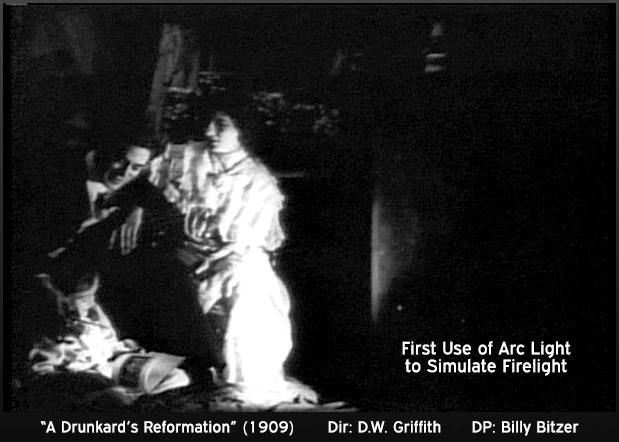

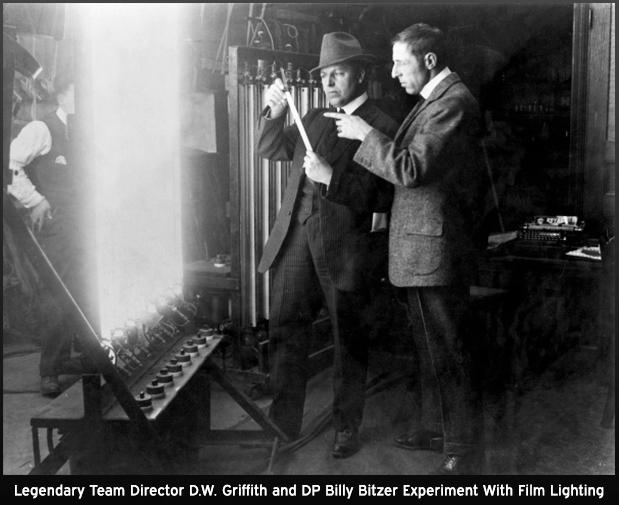

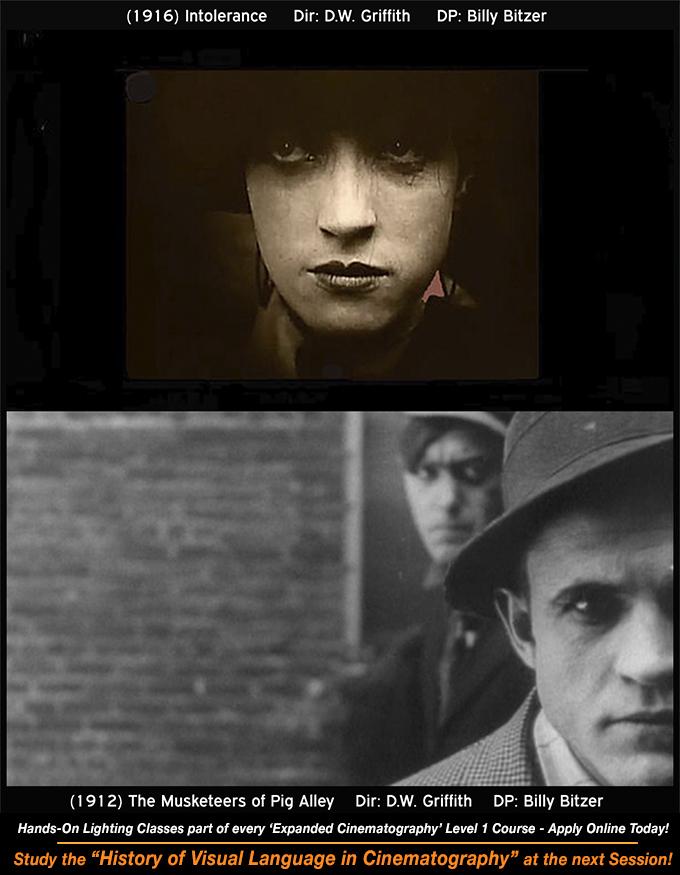

As early as 1909, Cinematographer Billy Bitzer, who distinguished himself for his work alongside D.W. Griffith on “Intolerance” (1916) and “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), experimented with atmospheric effects using artificial lights. In “A Drunkard’s Reformation” (1909), he put an arc light in the fireplace to simulate firelight.

The same year, he created a dawn lighting effect in “Pippa Passes” (1909) by moving an opaque panel in front of an arc to simulate the rising sun. Bitzer also experimented with shooting at lower light levels and later noted the difficulties because of the poor film stock.

Bitzer continued to experiment, and his discovery of backlight was the first step in overcoming the problem of screen depth. By rimming a subject with light on the off-camera side, a tonal difference was created between the subject and the background, making the subject appear separate and distinct.

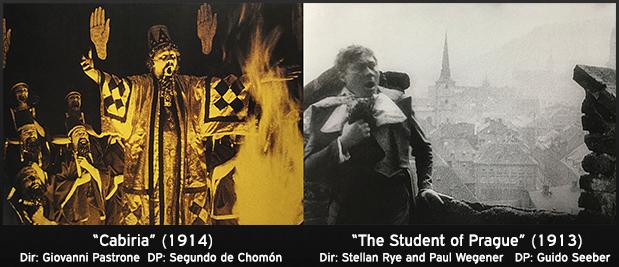

Across the Atlantic, the first ever traveling shot came in the Italian film – Cabiria” (1914) by Director Giovanni Pastrone and Cinematographer Segundo de Chomón. There had been films that used a dolly to achieve a simple movement, but it was “Cabiria” (1914) that first introduced a wandering camera that could travel both forward/backwards and side to side.

Across the Atlantic, the first ever traveling shot came in the Italian film – Cabiria” (1914) by Director Giovanni Pastrone and Cinematographer Segundo de Chomón. There had been films that used a dolly to achieve a simple movement, but it was “Cabiria” (1914) that first introduced a wandering camera that could travel both forward/backwards and side to side.

Near the same time, the use of perspective and skillful contrasts between light and dark in “The Student of Prague” (1913) by Cinematographer Guido Seeber of Germany raised the art of cinematography to the highest level yet seen.

These first cinematographers were looking for solutions to take what limited technology they had and create more and more expressive images from them. It is important to remember that these artists were working with materials and tools far less sophisticated than the digital camera in your phone, but nonetheless, they were able to make expressive and emotive images that stick with us and influence the art of cinema still to this day.

Viewing List:

The Student of Prague: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0003419

The Birth of the Nation: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0004972

Cabiria: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0003740

1915-1921

“The Birth of Style and the Discovering of Cinematic Language…”

As time went on, cameramen began looking for more ways to further distinguish their images. After backlight, the development of soft focus lenses and soft-focus attachments, such as gauzes or diffusion discs over the lens allowed for a completely different optical treatment. They were first used only for close-ups but gradually found wider application.

The softening effect allowed a blending of tones, a tendency toward luminous gray shades that dominated the image. The control of light and dark tones became more impressionistic and a more important clement in composition. Still photographers had known of the potential of soft-focus lenses were mass-produced for still photography by 1914 and were in use in motion pictures by 1915.

The softening effect allowed a blending of tones, a tendency toward luminous gray shades that dominated the image. The control of light and dark tones became more impressionistic and a more important clement in composition. Still photographers had known of the potential of soft-focus lenses were mass-produced for still photography by 1914 and were in use in motion pictures by 1915.

Around 1915, as films became longer and more complex, the cameraman began to acquire assistants to handle the different intricacies of the process. In “Birth of a Nation” (1915), specific scenes were tinted to “suggest” moods: the burning of Atlanta was tinted red, the night scenes, blue and the exterior love scenes pale yellow.

Together from 1908 to 1924, Griffith and Bitzer pushed American film in new directions. Griffith was constantly striving to make film a more realistic and expressive medium, and in Bitzer he found the perfect partner. Through experimentation, ingenuity, and luck, Bitzer was able to bring Griffith’s suggestions and ideas to realization on film. Bitzer said, “What Mr. Griffith saw in his mind we put on the screen”. It was 1915 before the cameraman even began to receive screen credit as a common practice.

For “Intolerance” (1916), Griffith and Bitzer built a camera dolly 150 feet tall in order to dolly in and down from a wide shot of the entire Babylon set to the dancing virgins, then into the huge banquet hall, and finally ending on a tiny toy chariot. The dolly had an elevator to allow the camera platform to be lowered and was pushed by twenty-five men along a railroad track.

Numerous films around 1916, notably C. B. De Mille’s “Joan the Woman” (1916) and “Dream Girl” (1916), began to reflect a concern for mood and the expressive use of lighting.

Numerous films around 1916, notably C. B. De Mille’s “Joan the Woman” (1916) and “Dream Girl” (1916), began to reflect a concern for mood and the expressive use of lighting.

George Mitchell introduced the first Mitchell camera. While the Pathe and the Bell & Howell required focusing directly through the taking lens (after removing the film from the gate), the Mitchell movement mechanism could be racked to the side out of the line of view, allowing the luxury of direct through the lens focusing with a view finder. Bitzer and Griffith realized the fruits of their struggles in “Broken Blossoms” (1919), which demonstrates a successful creation of mood in scene after scene.

The American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) was created in 1919. Certainly until almost 1920, the cameraman was the controlling force in most productions. The necessary emphasis on visuals in silent films meant that the man commanding the visuals was of primary importance. Early film was also a very technical medium owing to deficiencies in equipment. The cameraman said what could and could not be done. As Joseph Ruttenberg recalls ‘The cameraman was God’.

By the end of WWI the cameraman had a wide range of arc lamps at his disposal most were in the IS-amp to ISO-amp range, but there were also 300-Amp military arcs, which could be used to simulate a single light source for interiors or exteriors. By the mid 1920’s the use of soft-focus lenses and soft-focused attachments were commonplace. The soft-focus close-up was to be a Hollywood trademark for almost thirty years.

Diffused cinematography may have been influenced by impressionist art. An example can be seen in Julius Jaenzon’s work on “Korkarlen” or “The Phantom Carriage” (1921). Vladimir Nilsen asserts that some significant techniques borrowed from the impressionists.

Diffused cinematography may have been influenced by impressionist art. An example can be seen in Julius Jaenzon’s work on “Korkarlen” or “The Phantom Carriage” (1921). Vladimir Nilsen asserts that some significant techniques borrowed from the impressionists.

The cameraman now had options other than flooding the set with lights. Seitz is credited with pioneering the concept of Key Lighting, which is standard practice today. Nilsen calls it (Seitz’s Theory) “The first theory of “studio lighting:” and it involved an adherence to the motivation of source of light. If there were a window on the set, all light would be motivated from the window. “The violation of this law was regarded as indicative of illiteracy.”

Viewing List:

Intolerance: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0006864

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0010323

The Phantom Carriage: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0012364

1922-1928

“The Early Troubles of Color and Sound”

Author and Film Critic Leonard Maltin was prompted to observe: By the 1920’s, Hollywood had reached the zenith in pictorial quality. Even unimportant “B” pictures were well photographed and elaborate major films had a luster that had never before been seen on the motion picture screen indeed, it is a quality Hollywood never really recaptured.

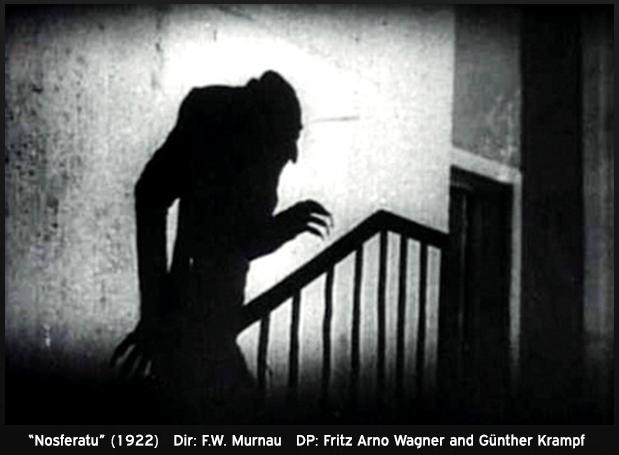

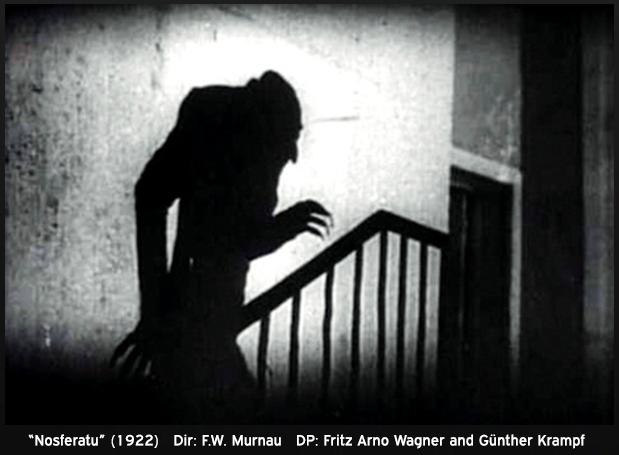

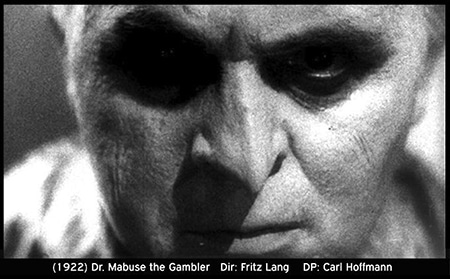

Every photographically educated cameraman was employing Bitzer’s back-lighting technique. The Separation and depth created by backlighting made it a necessity in the minds of most cameramen and they used illiberally on every scene. European influence on American cinematography came form the German expressionists. To be sure the Americans never approached the extremes of German films such as The Cabaret of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922) and other works of the early 1920s.

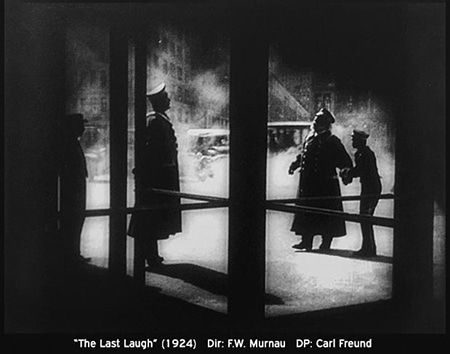

The European film that most influenced American cameramen was F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924). In the picture, cameraman Karl Freund created moods, which accurately reflected the feelings of the protagonist. It was also the first instance of using a handheld camera.

The European film that most influenced American cameramen was F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924). In the picture, cameraman Karl Freund created moods, which accurately reflected the feelings of the protagonist. It was also the first instance of using a handheld camera.

In the scene in which the doorman gets drunk, Freund created subjective point-of view shots by strapping the camera to his waist. In the film Entr’acte (1925) French Director Rene Clair put the camera on a roller coaster to achieve the effect.

By the mid-1920’s individual styles of various cameramen began to emerge: John Seitz’s use of the Rembrandt north light, the enchanting romanticism of Charles Rosher and Karl Struss, Lee Carmes’s personal adaptation of the north light approach, and William Daniels’ controlled mastery of filters and gauzes.

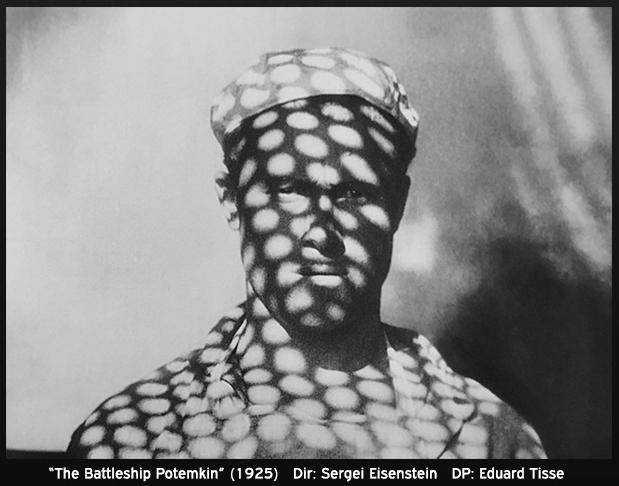

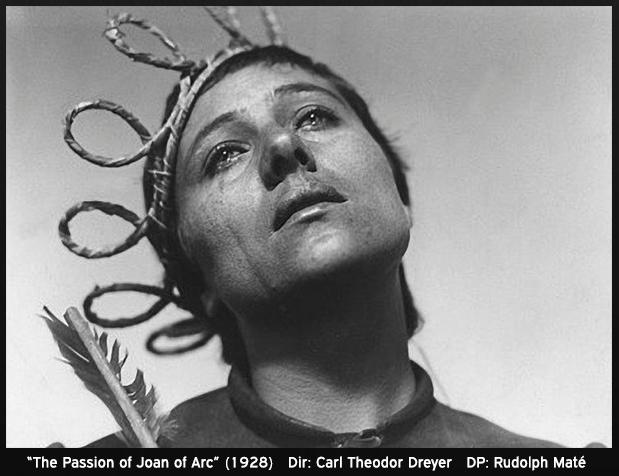

During this time period across the Atlantic the European countries also continued to push the bounds of cinematographic images with The Battleship Potemkin in Russia (1925), Faust in Germany (1925), and The Passion of Joan of Arc in France (1928).

Anamorphosing optics was developed by Henri Chretien during WWI to provide a wide-angle viewer for military tanks. In the 1920s, historic motion picture inventor Leon F. Douglass was able to adapt and create anamorphic motion picture cameras and lenses.

In 1922, the first color feature made in Hollywood, The Toll of the Sea (1922) was produced by Technicolor and released successfully. Other pictures, all or partially in color, soon followed, such as The Black Pirate (1926), but the lack of realistic color, because of the absence of blues, caused the color boom to decline.

In 1922, the first color feature made in Hollywood, The Toll of the Sea (1922) was produced by Technicolor and released successfully. Other pictures, all or partially in color, soon followed, such as The Black Pirate (1926), but the lack of realistic color, because of the absence of blues, caused the color boom to decline.

The arrival of sound presented another number of new challenges for the director and cinematographer. In Cinematographer Hal Mohr’s words, “The technicians from AT&T, the soundmen, said, ‘Look, you’re going to make talking pictures, you’re going to do it the way we say it can be done, regardless of what you’ve been doing.”

As incandescent lighting was further developed in the 1930s, the introduction of the optical printer in the late 1920’s put a stop to the optical effects created in the camera. American Cinematographer writes: It provided a new found flexibility in lighting which gave the director of photography heretofore unequaled artistic and creative range, enabling him, almost literally, to paint with light. The directors and cinematographers joined forces to lead film away from the tyranny of sound, thus allowing the camera to reestablish itself as a creative tool.

Viewing List:

The Battleship Potemkin: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0015648

Faust in Germany: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0016847

The Passion of Joan of Arc: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0019254

1928 – 1939

“From the first Oscar to Color”

In 1928 the First Academy Award for Best Cinematography was given to Charles Rosher and Karl Struss for “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans.” Rosher and Struss gave the film a look that revolutionized much of the American cinema. Also, Director F. W. Murnau brought with him to Hollywood many technological innovations that the German cinema had pioneered.

By this time Eastman officially had introduced (Cine Negative) Panchromatic Type II. It had a much greater tonal range than any other film, thus, in James Wong Howe’s words, it “allowed the photographer to capture scenes more realistically.”

Technicolor developed a way to treat particular hues of the spectrum, but the lab strongly discouraged any experimentation with lighting.

In the beginning of the 1930’s Hollywood became a feudal state in which the studio heads wielded absolute power. Everyone else, producers, directors, stars, and cameramen, answered to the studio.

The studios started to see the cameraman, too, as a technician, a very vital technician whose importance was such that he was kept under contract. The contract frequently gave the cameraman political clout over directors who often were not under such commitments.

Technicolor encouraged overall flat lighting, using floodlights instead of spots. The color film stock was very slow (with an ASA of around 10) and balanced for daylight, thus necessitating the extensive use of white-flame arc lights. These arcs did not allow the control attainable with contemporary incandescent units.

The desire for a studio look also imposed restrictions on the cameraman. Each of the major studios, in particular, MGM, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, Warner Brothers, and Columbia, evolved a visual quality that was more or less distinctive to their films.

The films of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the glamor studio, were, in Baxter’s words, rich with “… a polish and technical virtuosity that is uncontested in the period. There is a brightly lit, sharp-edged intensity…” perfected by its cameramen William Daniels, Harold Rosson, George Folsey, and Joseph Ruttenberg.

Cameramen like Arthur Miller and Leon Shamroy lit the sets in a brilliantly clear, classically high-key approach which made the furniture shine and the sets sparkle to give the impression of luxury. But many refused to exploit the new potentials and shoot at lower light levels or with deeper focus. They overexposed and underdeveloped the negative to gain a flatter less contrasty image.

Many Cinematographers started to shoot at lower light levels, using high contrast to create “more naturalistic settings.” Such realism, however, would not become popular until the forties.” The film stock showcased in “Gone with the Wind” allowed contrast without the loss of detail and encouraged more lighting for dramatic effect.

In 1939, “Gone with the Wind” wins the Academy Award for Best Cinematography for a Color film. Starting the trend of having a Best Cinematography Award for Color and Black-and-White until 1967.

1940 – 1950

“From War to the Advancement of Color Film”

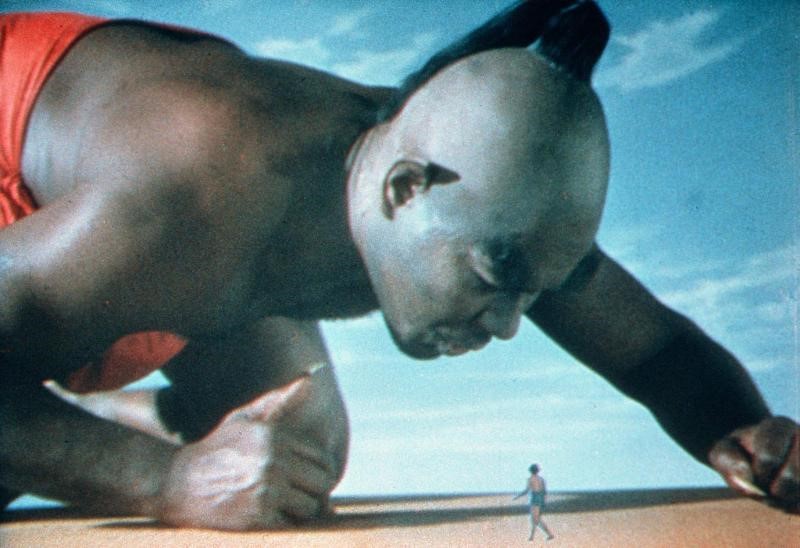

| “The Thief of Bagdad” (1940) DP: Georges Périnal Dir: Ludwig Berger, Micheal Powell, Tim Whelan |

In the early 1940’s different companies began to experiment with color film. In 1940, Agfa color negative-positive color material was used for the first time for a feature film “Frauen sind doch bessere Diplomaten” (Women are the better Diplomats) by the German UFA Production Company. Technicolor had developed monopack color in 1941, but the color quality was poor. It was used on several features, including “Dive Bomber,” “Lassie,” “Come Home,” and “King Solomon’s Mines,” but failed to generate much enthusiasm in the industry.

Gregg Toland’s tour de force, deep-focus photography of “Citizen Kane” (1941), is a film that took deep focus to its artistic extreme. Factors fostering Toland’s work were the introduction of coated wide-angle lenses, faster film (Super XX), and the new, powerful (22-amp) arc lights. Ralph Hogue and Toland developed Waterhouse stops which were a series of slides that could be put in a slot in the lens to provide exact iris settings. These allowed interiors to be shot at aperture openings as small as f22.

“Black Narcissus” (1947) DP: Jack Cardiff, OBE, BSC Dir: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

In 1942, owing to wartime, the United States government issued an order restricting the amount spent on any movie set to five thousand dollars.

“The Black Swan” (1942) DP: Leon Shamroy, ASC Dir: Henry King

An editorial in American Cinematographer expressed the frustration of cameramen over the studio restrictions: “… judged by the results on the screen, they [studios] seem to shackle these highly paid artists by insisting that all photography all the lot conform to rigid, if perhaps unwritten, regulations dictated by the personal preferences of someone in authority. The result is, photographically speaking, one picture from of these studios looks very much like other pictures from that studio.”

Neorealist photography characterized by the work of G.R. Aldo “La Terra Trema” (1942), moved into realms virtually unknown in Hollywood. Neorealism as Andre Bazin notes “creates an ambiguous reality. It is less stylized, more natural, stripped of expressionism.” The Neorealist insisted upon naturalistic source lighting, using natural light augmented by artificial lamps whenever possible, and doing away with all artificial backlights.

“How Green Was My Valley” (1941) DP: Arthur C. Miller, ASC Dir: John Ford” How Green Was My Valley” was the Academy Award Winner for the Black and White, where as “Citizen Kane” lensed by Gregg Toland, ASC and Directed by Orson Welles did not win.

“How Green Was My Valley” (1941) DP: Arthur C. Miller, ASC Dir: John Ford” How Green Was My Valley” was the Academy Award Winner for the Black and White, where as “Citizen Kane” lensed by Gregg Toland, ASC and Directed by Orson Welles did not win.

In 1947 Higham and Greenberg write, “The forties may now be seen as the apotheosis of the U.S. feature film, its last great show of confidence and skill before it virtually succumbed artistically to tile paralyzing effects of bigger and bigger screen, and the collapse of the star system.”

By 1948 consent decrees resulted in cameramen, as well as stars and other artists, losing their studio contracts. The cameraman consequently lost some of his influence around the lot.

“The Third Man” (1949) DP: Robert Krasker, ASC, BSC Dir: Carol Reed

1940 – 1950 In the early 1940’s different companies began to experiment with color film. In 1940, Agfa color negative-positive color material was used for the first time for a feature film “Frauen sind doch bessere Diplomaten” (Women are the better Diplomats) by the German UFA Production Company. Technicolor had developed monopack color in 1941, but the color quality was poor. It was used on several features, including “Dive Bomber,” “Lassie,” “Come Home,” and “King Solomon’s Mines,” but failed to generate much enthusiasm in the industry. |

Gregg Toland’s tour de force, deep-focus photography of “Citizen Kane” (1941), is a film that took deep focus to its artistic extreme. Factors fostering Toland’s work were the introduction of coated wide-angle lenses, faster film (Super XX), and the new, powerful (22-amp) arc lights. Ralph Hogue and Toland developed Waterhouse stops which were a series of slides that could be put in a slot in the lens to provide exact iris settings. These allowed interiors to be shot at aperture openings as small as f22. |

|

In 1942, owing to wartime, the United States government issued an order restricting the amount spent on any movie set to five thousand dollars. |

An editorial in American Cinematographer expressed the frustration of cameramen over the studio restrictions: “… judged by the results on the screen, they [studios] seem to shackle these highly paid artists by insisting that all photography all the lot conform to rigid, if perhaps unwritten, regulations dictated by the personal preferences of someone in authority. The result is, photographically speaking, one picture from of these studios looks very much like other pictures from that studio.” Neorealist photography characterized by the work of G.R. Aldo “La Terra Trema” (1942), moved into realms virtually unknown in Hollywood. Neorealism as Andre Bazin notes “creates an ambiguous reality. It is less stylized, more natural, stripped of expressionism.” The Neorealist insisted upon naturalistic source lighting, using natural light augmented by artificial lamps whenever possible, and doing away with all artificial backlights. |

|

|

|

In 1947 Higham and Greenberg write, “The forties may now be seen as the apotheosis of the U.S. feature film, its last great show of confidence and skill before it virtually succumbed artistically to tile paralyzing effects of bigger and bigger screen, and the collapse of the star system.” By 1948 consent decrees resulted in cameramen, as well as stars and other artists, losing their studio contracts. The cameraman consequently lost some of his influence around the lot. |

|