source- GCI http://globalcinematography.com

I did my first interview with Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC in 1978 about his collaboration with Francis Ford Coppola on the production of the Apocalypse Now. At the beginning of our conversation, Vittorio suggested that I ask why he shot scenes the way he did rather than how. He, Coppola and the movie earned Academy

Awards. Vittorio contacted me in 2012 to discuss his idea for creating a book dedicated to documenting the history of cinematography as a universal language for telling stories with moving images projected on cinema screens. He chose 150 cinematographers whose careers spanned the history of the cinema dating back to the first decade of the 1900s. The book is called The Art of Cinematography. Vittorio asked Lorenzo Codelli and me to each write 900-word profiles of 75 of those cinematographers, including how one of their films played a significant role in advancing the art form.

See related content about the book: ARTICLE and VIDEO

My list began with Billy Bitzer, who began his career hand cranking black and white film through a handmade motion picture camera during the 1890s. He made intuitive decisions about using composition, light, shadows, darkness and focus to influence how audiences perceived and re-acted to scenes. The short, silent films were watched through a window on a hand-cranked projector in penny arcades. That was the dawn on the industry. Bitzer subsequently collaborated with director D.W. Griffith on the creation of such classic silent movies as The Birth of A Nation and Intolerance. No sound was needed to engage audiences.

The art and the craft of telling stories with moving images have evolved as a universal language. Conrad Hall, ASC created a memorable scene in In Cold Blood in 1968. An actor was portraying a murderer in a jail cell who was confessing his crime to a chaplain. There was a window in the background. Conrad intuitively sprayed water on the top of the window. The water rolled down the window like rain. Conrad angled light from outside the window into the cell in a way that caused streams of water to cast shadows that looked like tears on the prisoner’s face.

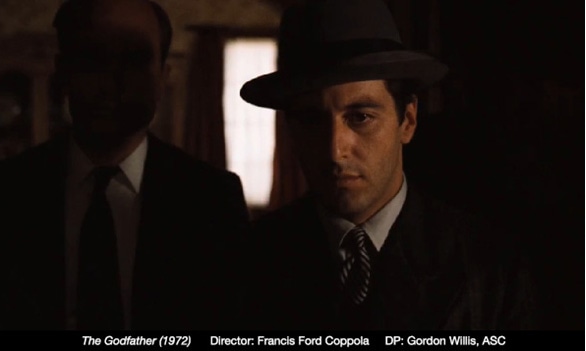

Gordon Willis, ASC collaborated with director Francis Ford Coppola on the production of The Godfather in 1972. Marlon Brando was cast in the role of Mafia boss Don Corleone. In various scenes, Gordon created shadows to mask Corleone’s eyes to conceal what he was thinking. It was an intuitive decision that was artfully executed. The Godfather earned 10 Academy Awards including best picture, actor and director. Gordon’s wasn’t recognized because his artful cinematography was transparent. It wasn’t obvious to critics that the director embraced Gordon’s unique talent for augmenting settings and emotions by composing shots from the right angles coupled with artful composition, focus and use of light and shadows. In 2010, the Academy of Motion Arts and Sciences presented an Honorary Oscar to Gordon Willis for “unsurpassed mastery of light, shadows, color and motion”. |  |

Flashback to 1974: Management at Paramount Pictures sponsored a quest by director Douglas Trumbull to create the ultimate cinema experience for audiences watching moving images projected on cinema screens. Douglas shot tests in various formats before concluding that the ultimate aesthetic experience was recorded on 65 mm color negative film exposed at 60 frames per second. The edited film was projected in 70 mm print format at 60 frames per second. He called it the Showscan format. Watching the film projected on a cinema screen was like being there when the action was happening. Unfortunately, executives at the studio decided it would be too expensive to produce and distribute movies in Showscan format. Douglas produced several nature films in Showscan format that mesmerized audiences at theme parks.

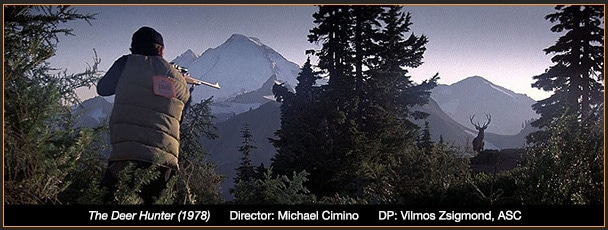

| I did my first interview with Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC about his collaboration with director Michael Cimino on the production of The Deer Hunter in 1978. They spent five months shooting the film at practical locations ranging from a steel mill to a forest in Africa. I asked how they shot specific scenes, and why they filmed them that way. Vilmos replied that he knew the emotions they wanted to evoke and trusted his instincts to visually augment the performances. The Deer Hunter earned six academy awards, including best picture, cinematography and director. |

I asked Sven Nykvist, ASC to share an insight about the role that cinematographers play in the collaborative art and craft of film making in 1979. Sven responded, “It is important to light so audiences can see the truth about characters through their eyes and faces and to use shadows to conceal their feelings and thoughts.”

Russ Carpenter, ASC collaborated with director James Cameron on the production of Titanic in 1997. It was the story of the interactions between passengers onboard a luxury ship crossing the ocean and the tragedy that ensued after the boat hit an iceberg and sank. It was an absolutely compelling drama. The live action scenes were produced in Super 35 film format. I interviewed Russ and Jim together. When I asked Russ to share his memories and feelings, he replied, “Titanic is a love story on an epic scale with spectacular visual effects. The computer is an amazing tool, but a well-lit close-up of characters can be just as powerful and compelling as a sinking ship. In the end, what moves me the most are images that are visual poetry. Capturing the twinkle in Kate Winslet’s eyes and the radiance of her skin tones and the electric energy of Leonardo DiCaprio. For me, a close-up is an opportunity to enter the soul of another human being.” When I asked Cameron if he could describe the meaning of the film in one sentence, he replied, “Unquestioning belief in technology sank this ship.” Titanic earned 11 Oscars, including best picture, director and cinematographer.