On December 4th 2024, Dr. Charles Poynton (IMAGO Technical Committee (ITC) associate member) hosted a day for industry experts about the topic of metamerism in London. Miga Bär (NSC and ITC associate member), Christian Wieberg-Nielsen (FNF and ITC member) and Veronica Tiron (ADIT member) attended the day and collected their notes to share this debrief with all IMAGO members.

1. Introduction

You might’ve noticed the word ‘metamerism’ pop up more and more often in our industry over the last few years. Especially in relation to using LED lighting on set or screening your film in a laser cinema, it’s almost a given that someone will mention metamerism at some point. It seems to be a bit of a buzzword when we’re talking about any type of colour representation mishaps. This begs the question if talking about metamerism is just a hype or if there is a reason that we see this mysterious word come up more frequently.

To answer this and many other questions, Dr. Charles Poynton hosted a one-day event called Metamerism Experts’ Day at Technicolor in London on 4 December 2024. The idea of the day was to come together with a group of around 30 industry experts in the realm of colour and imaging science, camera technology and production workflows to confirm what we know metamerism to be, how we encounter it in motion picture imaging and what problems with metamerism we face currently. The impressive list of speakers invited for the day included:

- Charles Poynton renowned colour scientist and mathematician

- Andrew Stockman professor of vision science at UCL London

- Laurens Orij colourist and colour scientist

- Andy Rider research associate at UCL London

- John Frith imaging engineer at MPC/Technicolor

- Daniele Siragusano imaging engineer at Filmlight

- Bram Desmet CEO at Flanders Scientific

- Jean-Philippe Jacquemin Product Manager HDR at Barco

In addition to the speakers, most of the participants came from similar professional backgrounds, making this event a true gathering of experts. For many of us, it felt like an all star ‘nerdfest’ in the best possible way.

Trying to sum up the incredible wealth of information shared throughout the day, both by the presenters and in discussions between all participants in the workshop is an impossible task. We’ll give it a shot nonetheless, to hopefully spark some interest in the various topics presented throughout the day.

2. Metamerism and metameric failure

Presentations by Charles Poynton and Andrew Stockman

The official definition of metamerism by the CIE (Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage) goes as follows:

Property of spectrally different colour stimuli that have the same tristimulus values in a specified colourimetric system.

That’s a rather cryptic description though, so let’s try to dissect that a bit. The colours we see are created when light with a specific spectral power distribution enters our eyes and is interpreted by the human visual system, forming an image in our minds.

One of the first challenges to overcome in this process is that the visible spectrum contains many different wavelengths from the electromagnetic spectrum. The human eye on the other hand is a tristimulus mechanism that, with its 3 different cone types, responds to 3 particular areas in this spectrum. These peaks in our cone sensitivity happen to be around the yellow, green and violet parts of the visible spectrum. In other words, our brain combines signals from the three types of cones to create the perception of a full range of colors, but there is no information about actual wavelengths if light anymore at that point. A visual illustration of these concepts can be found in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: An illustration of the electromagnetic spectrum and a close-up of the human visible spectrum within it

(Image source: Centre for Disease Control, US Government)

Metamerism happens when two so-called stimuli1 that are actually made of different wavelengths (in scientific terms: two stimuli that are spectrally different) end up looking the same to our eyes (and brain). In other words, even though they’re not spectrally identical, our vision processes them in a way that makes them appear indistinguishable to us in certain lighting or viewing conditions. These two stimuli would be called metamers.

This in itself is a nice bit of trivia knowledge for Friday night drinks, but doesn’t do that much for us yet. It’s when metamerism goes wrong that we start to care about it. And when this happens we talk about metameric failure or metameric mismatch. Obviously, even though the workshop was called Metamerism Experts’ Day, the day was mostly about when the train goes off the tracks and metameric failure arises. We will share some examples throughout the rest of this document.

Figure 2: Human vision LMS cone response per wavelength (image source: Wikipedia)

2.1 Simple observer metamerism

Presentation by Laurens Orij

A simple example to start demonstrating the definition of metamerism and metameric failure, and to start understanding why it matters is the – by now quite famous – bell pepper experiment. In this experiment we start by pointing two spectrally different light sources at a large white surface, for instance a tungsten light source and an RGB LED light source. The spectral power distribution of these two sources would look something like what is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Spectral distribution of a tungsten light source vs an RGB LED light source. These are emulated SPD’s for illustrative purposes only, not actual measurement (Image source: Miga Bär)

Even though the light sources have very different spectra, we could still make the light they produce appear the same. By mixing in the right amounts of R, G and B on the LED light, we create a white light that looks the same as the tungsten light, even though the spectral distribution of both sources are very different. When that is achieved we have an example of metamerism, where two different spectral sources result in the same colour and light hitting our eye. Figure 4 provides a schematic representation of this concept.

The key thing in this example is that our eye only measures the reflection of light off an object, not the physical properties of the light source hitting that object. In other words, if we have a white background it will appear the same when the mixture of red, green and blue light from the LED fixture creates the same reflection values off of the white surface as the tungsten light does and thus creates the same cone response in our eyes.

Figure 4: Top: Spectral distribution of two different light sources. Bottom: The measured values of both light sources, shown as RGB bars and a colour patch. (Image source: Gunther, L (2019), “The physics of music and color”. Springer, Cham)

Now, in the same setup, we would grab a handful of bell peppers, some red and some orange. When held in front of the tungsten light source, we see orange and red bell peppers. When we move the bell peppers to the RGB LED light source though, all the bell peppers will turn red (see figure 5). This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the tungsten light’s spectral distribution was quite evenly distributed over all wavelengths, while the RGB LED light doesn’t emit any orange wavelengths towards the bell peppers, and thus the orange can’t be reflected. This results in a different cone response in our eyes, which is why we see a difference. Although this is technically not an example of metameric failure – after all, when measuring the spectral response of the orange bell pepper under both lights will result in two different graphs – it is a very clear example that two lights creating metamers when aimed at one particular surface, might not be metameric when lighting a different object.

Figure 5: The same bell pepper illuminated under two different light sources (image source: Laurens Orij)

If we take the above example and extrapolate that to our day to day in the film industry, we become aware that one of the dominant colours in most skin tones is orange. That said, putting a person in front of those two different light sources that both created a 3200 Kelvin light, will result in two very different representations of that person’s skin tones. Under the RGB LED light, the person’s skin will look unhealthy, often with a magenta cast. Because there was no orange light to reflect off of the skin, we will have a very hard time making this person look any better during colour grading. An example of this effect can be seen in figure 6, where the LED light’s spectral power distribution wasn’t as poor as in the bell pepper example, but still uneven enough to make it challenging to make the model’s skin look good in colour grading.

Figure 6: A model illuminated by a tungsten light (left) and the same model illuminated by a sub-optimal LED light source (right). (image source: Conference of lights – Berlin 2019)

The bottom line is that the spectral distribution of light sources directly impacts how colours are reflected off of surfaces. If the light source doesn’t emit certain wavelengths, those wavelengths can’t be reflected by objects either. The bell pepper experiment is a striking example of how this effect might not be obvious immediately but can cause significant issues in practice.

Fortunately, most LED light manufacturers have by now moved on to producing lighting fixtures that include more colours than just the pure RGB LEDs, enabling fuller spectrum light distribution. Nonetheless, it is important to test lights in different setups to really know what they do with the surface colours of your scene.

2.2 Metamerism in digital cinema cameras

Presentations by Charles Poynton and Laurens Orij

In the second session of the day, things were taken one step further. As a next step a camera was introduced into the chain, as we tend to do when making films. Now instead of a light source illuminating a scene that is being observed by our eyes and brains, we now add a camera as an intermediary observer that records the scene.

As is the case with the human eye, almost all cameras we use today are so-called tristimulus devices, which means that they are sensitive to three specific parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, and will use these three different spectral sensitivities to mix different colours. In human vision we talk about the three different types of cones that are sensitive to Long, Medium and Short wavelengths, in other words LMS response. In camera sensors the three photosites are typically sensitive to Red, Green or Blue, or RGB. There is a large overlap between these two approaches, but there are also two big differences. First, the L cones are actually most sensitive in the yellow part of the spectrum as opposed to the red part that the R in RGB is geared towards. But besides that, the L and M cones in the human eye have a very large overlap in bandwidths they are sensitive to, as we already saw in figure 2.

Evolution has helped us humans to make sense of these two different yet very similar cone responses. When talking about technological solutions on the other hand, this is not ideal, since the large overlap between the Red and Green channels in a camera sensor would introduce a lot of noise and poor colour separation. Therefore camera manufacturers would typically spread out the response of the R, G and B sensor elements to get a more uniform distribution of the wavelengths. Figure 7 shows an example of the spectral response measurements of an Arri Alexa camera for instance. We can clearly see that the three stimuli are more evenly spread out and that there are larger parts of the bell curves that are mostly separate from the other two bell curves.

Figure 7: Measured spectral response of a professional digital cinema camera (image source: ACES Central)

Another conundrum when talking about cameras is the fact that a camera sensor doesn’t have a colour space in the same way that we are commonly taught to think about colourspaces. The photosites are being excited by light and register a specific intensity, but the sensor’s response can’t inherently be written down as an RGB value in and by itself. It’s only during the conversion from RAW camera data to a video file – either in camera or during post production – that the raw sensor responses are transformed into RGB values within a specific color space, typically defined by the camera manufacturer. Laurens Orij presented the outcomes of his research on a camera’s sensor spectral sensitivity and how it relates to the RGB gamut. To achieve this, he built a custom matte box with diffraction grating in it, to let the camera basically perform as a spectroscope. Using this technique and bypassing certain internal camera processes he was able to measure the full spectral response of the camera’s sensor, one wavelength at a time. When these sensor responses are mapped onto the CIE 1931 chromaticity chart (see figure 8), it becomes clear that the conversion from a camera sensor into tristimulus values can sometimes create values that are outside those defined in standard models of human visual perception. This outcome highlights a fundamental limitation of the CIE 1931 standard. Such anomalies can be displayed as clipped and unpleasing colours that are oftentimes hard to manipulate in post processing. The most common example of this is the extreme blue and violet hues we would sometimes get with highly saturated images processed in the ACES colour framework. These mishaps are also due to metameric mismatches, though they are happening mostly inside the camera. Laurens did not disclose which specific camera was used in the experiment, as the plausible assumption is that this type of behaviour will be happening in all professional digital cinema cameras.

Figure 8: Raw camera data plotted into CIE 1931 graph (image source: Laurens Orij)

No camera we use today captures the world exactly as our eyes see it. This inherent metameric mismatch is something we constantly deal with. While colour grading and colour management help compensate for this discrepancy, issues can still arise. The good news is that workarounds have been found for most camera metameric issues, meaning that as a filmmaker you won’t really notice that these issues take place. At the same time, it is good to be aware that because of technical or mathematical limitations, a camera will never fully reproduce the scene as you see it with your eyes, as long as we don’t update our standards. Even now that we see a push towards Rec2020 as the container for our deliverables, this doesn’t fix the issues as they are described above, as we can see that the issues stem from a mismatch between how different wavelengths of light are being measured rather than which triangle we draw within the CIE1931 diagram.

2.3 How metamerism relates to on-set and in-camera practices

Presentations by Charles Poynton and Laurens Orij

So then, where does this whole metamerism thing become an issue for us when shooting our productions, you might ask. And even though the majority of actual issues we find today are found in the realm of display technology, there are still a few areas where as a cinematographer, gaffer, production designer, costume designer or make-up artist – amongst others – it is good to be aware of the chances for metameric failure. This essentially all comes down to the spectral distribution of our light sources. And for the purpose of this topic, the term ‘light source’ also includes outliers like LED walls and rear projection that takes place on-set.

As described above, it is very possible to get unwanted results and unpleasant looking images when a light source is lacking specific wavelengths of light. We saw this with the bell pepper experiment but immediately realised we could extrapolate this effect to skin tones as well, which is typically the most important part of a lot of our images. With the bell pepper experiment the disastrous effect of that specific lighting fixture was immediately visible in front of our eyes and thus would be pretty easy to spot when it’s happening on-set. What complicates things a bit more is that, as discussed, we shouldn’t just judge the scene lighting with our eyes, but also see how our camera responds to the scene lighting and how our colour processing or colour management during post production will influence the lighting on-set. Therefore it is pivotal to have at least one decently calibrated monitor on-set, on which the image is watched through the same pipeline as will be used during post production. This ensures we can see a decent representation of what effect certain lights will have on the scene. This is primarily relevant when you are working with lighting fixtures that are known to have strong spikes in their spectral power distribution, like RGB LED lights, some lower quality CRI LED fixtures, and fluorescent lights for instance. Examples of different spectral power distributions are shown in figure 9.

Figure 9: The spectral distribution of various light sources (image source: Abdel-Rahman, F. et al (2017): “Caenorhabditis elegans as a model to study the impact of exposure to light emitting diode (LED) domestic lighting, Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A, 52:5, 433-43)

When shooting in front of an LED backdrop (often referred to as shooting in a volume, virtual production or in-camera VFX), this specific example of metameric failure becomes extra pronounced. For the LED wall to give a pleasing result in camera it needs to be calibrated with the camera basically being used as a colorimeter. If this is done well, the images shown on the LED wall can match perfectly in terms of colours with the foreground actors and props. To the naked eye though, this could look completely wrong, as the LED wall is being calibrated to be metameric with the camera’s spectral response, not with human vision. Figure 10 clearly shows an example of what the LED wall looked like on-set vs what the actual images in camera looked like. It’s easy to imagine that such a thing happening in front of an entire crew can cause a bit of confusion. In such a case it’s crucial to direct everyone towards a trusted monitor to get a sense of what the camera is seeing. Long story short, when looking at spectral distributions on-set, don’t trust your eyes to spot metameric issues, but use your colour managed signal from the camera as a final measurement device.

Figure 10: Set photo and a photo of the image as seen by the camera of the exact same setup and lighting (Image source: Mick van Rossum)

3. Metamerism and new display technologies

Presentations by Andy Rider, John Frith, Andrew Stockman, Bram Desmet, Daniele Siragusano and Jean-Philippe Jacquemin

All of the above was quite interesting and a great refresher of what most participants in the workshop were already aware of to some degree. At the same time they were just the opening act, as the talks about new display technologies like laser projection and QD (o)led monitors were clearly the main attraction of the day. This included various different presentations of which we will try to give a somewhat faithful summary here.

3.1 CIE 1931 and standard observer metameric failure

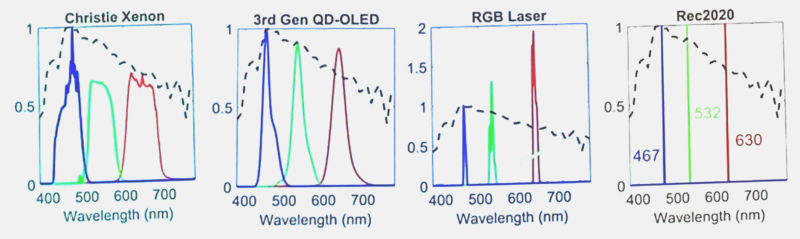

As mentioned in the chapter about camera metamerism, for most of our colour measurements, software and colour tools we rely heavily on the CIE 1931 model and underlying mathematical framework. This standard defines an ‘average’ or standard observer that we typically use as a representative for a human observer. This standard observer’s capabilities of seeing and discerning colours is based on experiments and calculations from the late twenties and early thirties of the previous century. It’s fair to say that this standard arose in a time when extremely narrow bandwidth light emitters were not a primary concern yet. Now that we do see a move towards displays that use very narrow bandwidth light sources like RGB lasers and QD (o)led displays, the shortcomings and flaws of the CIE 1931 model become evident. Specifically, the mathematical functions that are a core part of the CIE 1931 model contain errors that complicate accurately representing human colour perception under these conditions. This in turn can lead to metameric failure, or observable discrepancies between a spectrometer reading and human visual perception. Our eyes often see colours differently than what a spectrometer predicts using CIE 1931 xy coordinates during calibration. This failure gets worse as the bandwidth of our light sources becomes narrower. See figure 11 for examples of some different display types’ spectral power distributions.

Figure 11: Spectral power distributions of the RGB primaries of 3 different types of physical displays and a theoretical mapping of the Rec2020 primaries to a spectral power distribution. (Image source: Andy Rider, UCL)

Testing and research on this discrepancy has been conducted by Jean-Philippe Jacquemin at Barco, Daniele Siragusano at Filmlight and John Frith at Technicolor/MPC in London. They arranged a setup with a xenon projector and an RGB laser projector placed side by side. A group of professional observers, including colourists and DOPs, used colour grading tools specifically designed for this experiment to match a series of colour patches as they appeared simultaneously on both display technologies. As a result of this research, Barco has released a metameric offset correction (MOC) that can be applied to their laser projectors that are being installed in post production environments, to partially remedy this issue2.

3.2 Individual observer metameric failure

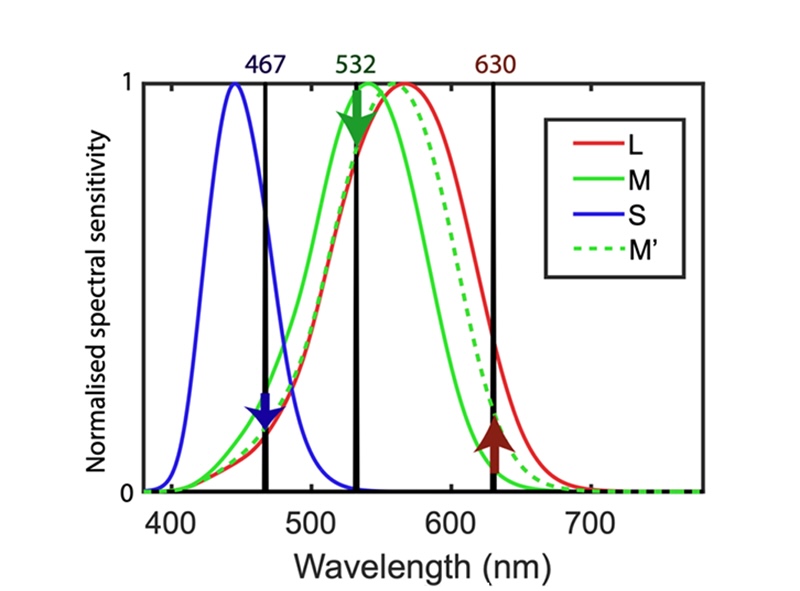

Besides the problems with measuring narrow band displays using the CIE 1931 standard observer, the mentioned research also started to show that there seem to be non-trivial differences in colour perception of these narrow bandwidth displays between different individuals. Research into this topic is ongoing by Andrew Stockman and Andy Rider from the Institute of Ophthalmology at University College London (UCL) with the support of John Frith.3. Early findings show clearly that colour vision deficient observers (e.g. those with conditions like deuteranomaly or protanomaly4) perceive a different white balance on a laser projector compared to broader-spectrum xenon projectors. For example, a deuteranomalous observer – who has difficulty distinguishing green from red due to a shifted M-cone response – experiences white balance shifts when viewing a laser projector. The effect of this can be seen in figure 12, where the spectral response of the LMS cones of someone without colour deficiencies are compared to the response of a colour deficient observer.

Figure 12: The spectral response of the LMS cones of an average observer compared to the spectral response of a deuteranomalous observer. (Image source: Andy Rider, UCL)

The diagrams in figure 12 shows the spectral response of an observer with normal colour vision (solid red, green and blue curves) as well as the shifted M’-cone sensitivity of a representative deuteranomalous observer (dashed green curve). The black vertical lines show the implicit wavelengths of the Rec.2020 colour space. Red, green and blue arrows show that for the anomalous observer the red light will produce a larger M’-cone response, while the green and blue will produce weaker responses. The overall effect is that the white balance will be shifted towards magenta. An illustration of what this colour deficient observer will perceive can be seen in figure 13, where a butterfly image is presented of a Kodak Digital LAD or Marcie chart in a neutral state (i.e. the way most people will see the image on a correctly calibrated RGB laser projector) and the same chart in the state how an observer with a deuteranomalous colour deficiency will perceive the image. It is important to stress that this deviation that a colour deficient person will see is not just how they always perceive the world. They actually see a dramatic change between the outside world and the image on display, where the extent of the shift is roughly illustrated in figure 13.

Figure 13: Butterfly image of a Kodak Digital LAD or Marcie chart that shows an estimated representation of a neutral image on the left side and an estimation of how different the image will look for a deuteranomalous observe when looking at in on an RGB laser projector on the right side (Image source: John Frith)

All of this relates to a presentation that Andrew Stockman gave earlier in the day that took a deep dive into the biochemistry of the human eye. He highlighted the role of chromophores and opsin proteins, two of the core elements of our cones that are responsible for colour sensation. Due to genetic variations in the opsin proteins that influence cone sensitivity, some individuals are more susceptible to experiencing metameric failures than others. Research shows that men are more likely to suffer from colour vision defects than women (see figure 14). The reason for this difference is that most colour deficiencies are passed along through the X chromosomes. Since men only carry one X chromosome as opposed to the two X chromosomes that women have, this increases the likelihood of colour deficiencies being inherited by men and gives women slightly more genetic variability in cone sensitivities. An interesting side effect of this is that there is a very small part of the female population that have tetrachromatic vision, meaning that they carry four different cone types. Women with tetrachromatic vision might have an advantage in distinguishing subtle colour differences compared to men. More research in this field will help us to fully understand the details around and effects of tetrachromacy5.

Unfortunately, with narrow-band spectrum devices, the perceptual differences between observers create a unique challenge: the inability to truly share the same cinematic experience. As the saying goes, “Chacun son cinéma”—everyone has their own cinema. This poetic metaphor risks becoming a literal reality, as the industry grapples with a problem that could result not only in subjective interpretations of a film’s narrative but also in physically distinct visual experiences for each individual.

Figure 14: Slide from Andy Rider’s presentation showing the percentage of UK residents suffering from various forms of colour deficiencies, split between male and female population (image source: Andy Rider, UCL)

The research conducted by Andy Rider, Andrew Stockman and John Frith does make it clear that discrepancies in perception are also present between non-colour-deficient observers, although to a lesser extent6.

One effect they observe has to do with the fact that – due to aging – the lenses in our eyes gradually become more yellow over time. While the brain compensates for this by maintaining a consistent colour balance for everyday vision and broader spectral displays, narrow band light sources and displays cause a different effect to observers with different stages of the yellowing of the lens. Early research by Andy Rider highlights a green/magenta shift in colour perception with narrow band light sources, not dissimilar to how a colour deficient observer sees images projected this way.

In cinema distribution, the expectation is that non-colour-deficient viewers are unlikely to experience significant issues, as they will adapt to the small shift they will see. While colour-deficient viewers will notice big discrepancies in the perceived white balance, anecdotal evidence suggests they adapt to some degree over time in the controlled environment of a cinema, where the screen is the sole light source.

Similarly, individuals with aging eyes may initially experience a noticeable white balance shift when viewing images in the theatre with narrow band laser sources, although further research is needed to confirm the extent and implications of these findings7.

What is currently still unknown is what the threshold is for acceptable deviations and when it becomes too much. For this to be set in stone the research needs to be expanded with a larger sample pool of observers as well as experiments with multiple different display technologies. Let this document also be an open call for any deuteranomalous and protanomalous people out there to reach out to the Institute of Ophthalmology at UCL, Professor Stockman needs you!8

Further research can both verify the calculations that UCL has made up to now as well as define what the threshold for acceptable deviations will be. For instance, experiments up to now have all revolved around RGB laser projection. The assumption is that QD (o)led monitors will show similar behaviour, but not enough research has been done yet to state this as a matter of fact.

4. Conclusions from the day

With a slight sense of drama we can say that the CIE 1931 standard is broken and no longer sufficient for the new technologies we face today, but luckily there is a potential alternative in the newer, improved CIE 2006 and 2015 standards. This realisation is incredibly problematic though as our entire industry is built on the underlying maths of this standard. Moving to a new standard, even if we knew what that standard should be, isn’t a trivial thing. It would require all software and hardware manufacturers to strip down all of the mathematics in their products and essentially start from scratch. It is fair to say that no-one can fully oversee the consequences of such an overhaul. This deserves extensive debate within various industry standards bodies to decide if it is even feasible to consider moving to a different standard over time.

Meanwhile, our industry should evaluate whether the advantages of narrow band displays – such as lower power consumption, coverage of the full Rec. 2020 colour gamut, higher peak brightness – outweigh the potential drawbacks of more frequent metameric mismatches and inter-observer issues. After all, in our field of work it is crucial to be able to trust that what you are seeing is also what the other people in the room are seeing. When we can’t trust that there is consistency between observers in how they perceive images, this creates uncertainty and confusion about creative conversations around the aesthetics of the image. A concrete example would be where there is uncertainty in a grading room whether a skin tone is judged negatively because of the perceived colour shift or simply because of personal preference. This situation could introduce inconsistent decisions and confusion. The current state of the research suggests that with narrow band displays there is an increased potential for these types of confusion when sat in a room with a group of key creatives in different age ranges and with different levels of colour deficiency.

When talking about potential solutions for the issues that the research suggests, it is important to realise that we as filmmakers don’t necessarily always have the full attention of display manufacturers. These companies have a plethora of interests to take into account, and it’s safe to assume that making filmmakers happy isn’t necessarily the top priority. That said, there are some potential solutions that could mitigate the stated issues. To wrap up the day we briefly discussed some of these solutions but also concluded that a deeper dive into problem solving could and should be the topic of Metamerism Experts’ Day 2025.

Potential solutions that were floated around the room included:

- On the side of lighting and LED walls the problems are understood and manufacturers are actively ensuring that newer models have better spectral power distribution. This seems to be a problem that is essentially already fixing itself.

- Improvements in laser projection technology, such as using six instead of three lasers for the primary colours9.

- Stop chasing full Rec 2020 coverage as a physical target. Rec 2020 was established as a container format that can encompass the largest possible amount of colours without introducing any imaginary or illegal colours, but it was not necessarily meant as a target to physically achieve with any display. As long as we are attempting to show colours that are closer to the corners of Rec 2020, it is certain that we are exacerbating the issue. The fact of the matter is that the primaries of Rec 2020 are all single wavelength points in the CIE 1931 chart, meaning that they can only be created by extremely narrow band light sources. And the narrower the lightsource, the bigger the risk of metameric failure.

- It is clear that more research and a wider sample group is needed to get an even better understanding of the scope and scale of some of the issues presented throughout the day.

All in all, Metamerism Experts’ Day 2024 was a unique opportunity to exchange knowledge and ideas between a group of industry professionals that – together – has quite the reach throughout our industry. And even though the conversations and presentations of this day only scratched the surface, our takeaway is that this day was a great starting point for what will hopefully become fruitful conversations and further research. There’s only one sentence that correctly wraps up the workshop as well as this document:

To be continued!

Footnotes

- Think of a stimulus as either a light source directly hitting the eye or light that is reflected off of an object and then hits the eye. In other words, it’s any object that emits or reflects light that we look at. ↩︎

- Link to white paper from Barco that describes the Metameric Offset Correction (MOC) http://bit.ly/4iWGGQR. ↩︎

- Link to press release about the ongoing UCL research: https://bit.ly/40ttR9D.

Earlier study of the Age Effect on Observer Colour Matching and Individual Colour Matching Functions

https://library.imaging.org/cic/articles/31/1/5 ↩︎ - Also commonly yet incorrectly referred to as ‘color blindness. ↩︎

- Andrew Stockman spoke about this topic at Camerimage 2024, a recording of the presentation can be found here: https://vimeo.com/1045953209?share=copy#t=3755.016. ↩︎

- Even though it wasn’t covered during the day, there is also interesting research by Trumpy et al on the same topic: https://www.mdpi.com/2313-433X/9/10/227 ↩︎

- The current state of the research performed by Andy Rider and Adrew Stockman can be found here: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10194574/. ↩︎

- Please contact John Frith () if you are a colour deficient person and want to participate in the research. ↩︎

- A display technology with extra primary colors reduces metameric failure.

David Long and Mark D. Fairchild, “Reducing Observer Metamerism in Wide‐Gamut Multiprimary Displays,” Program of Color Science, Rochester Institute of Technology, HVEI2015

https://s3.cad.rit.edu/cadgallery_production/storage/media/uploads/faculty-f-projects/1374/documents/249/hvei2015-long.pdf ↩︎

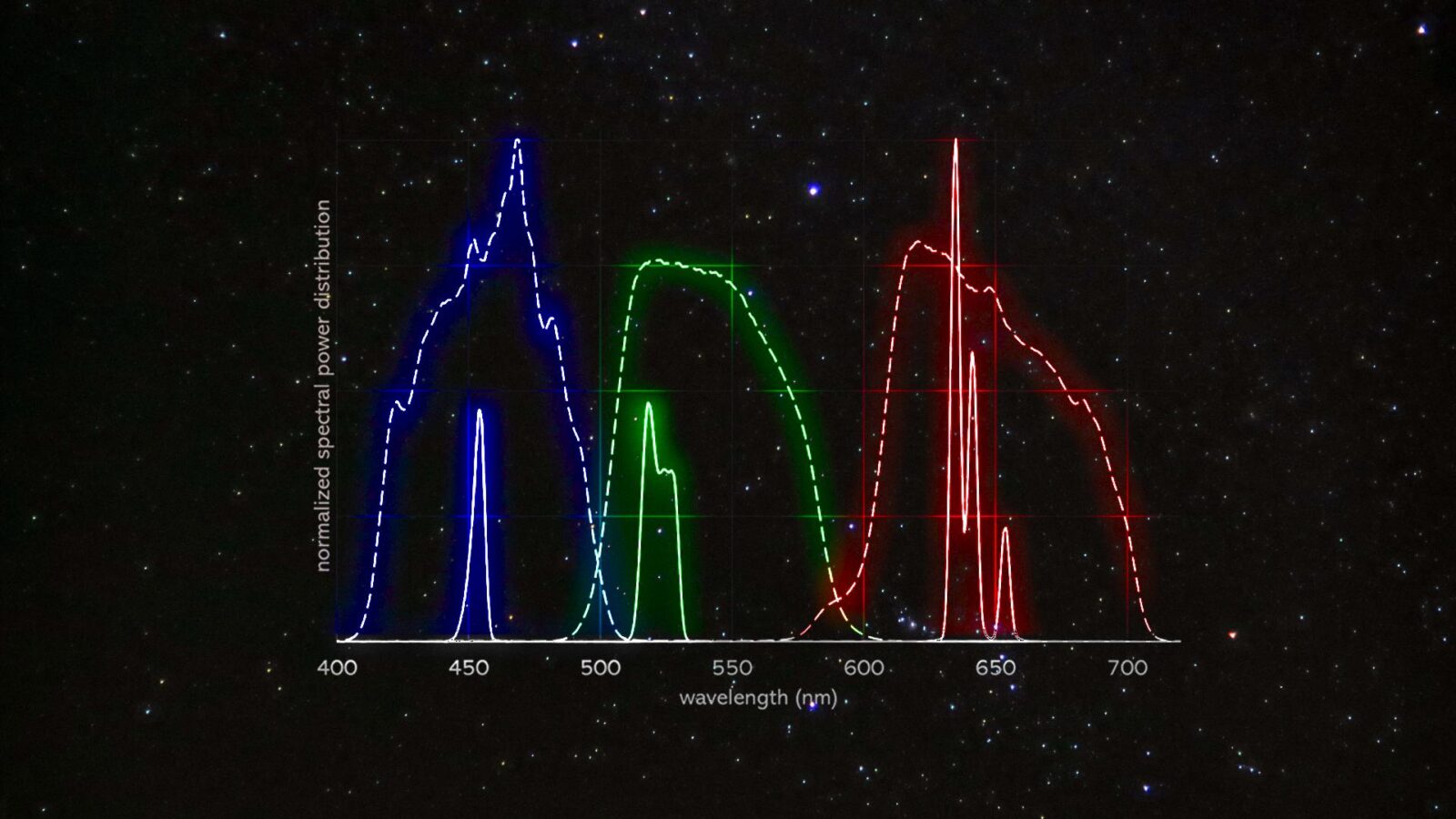

Spectral power distributions of the RGB primaries of a laser (solid lines) and a xenon-arc (dashed lines) DLP cinema projector in outer space

Mapping Quantitative Observer Metamerism of Displays, Trumpy et al. – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Spectral-power-distributions-of-the-RGB-primaries-of-a-laser-solid-lines-and-a_fig1_374863595